- Home

- Publications and statistics

- Publications

- Macroeconomic projections – June 2024

In order to contribute to the national and European economic debate, the Banque de France periodically publishes macroeconomic forecasts for France, constructed as part of the Eurosystem projection exercise and covering the current and two forthcoming years. Some of the publications also include an in-depth analysis of the results, along with focus articles on topics of interest.

Introduction

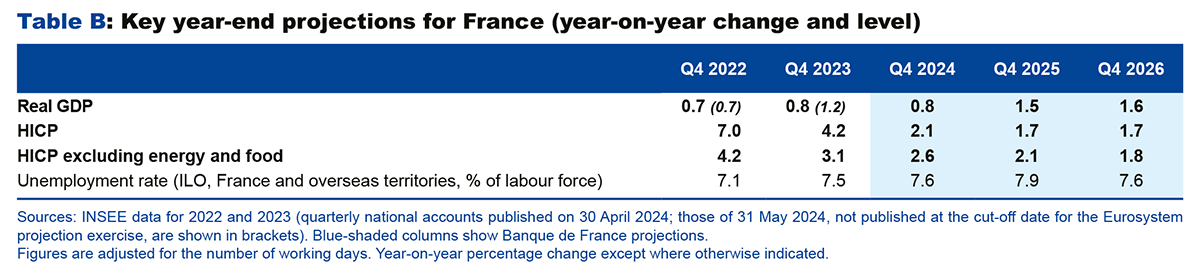

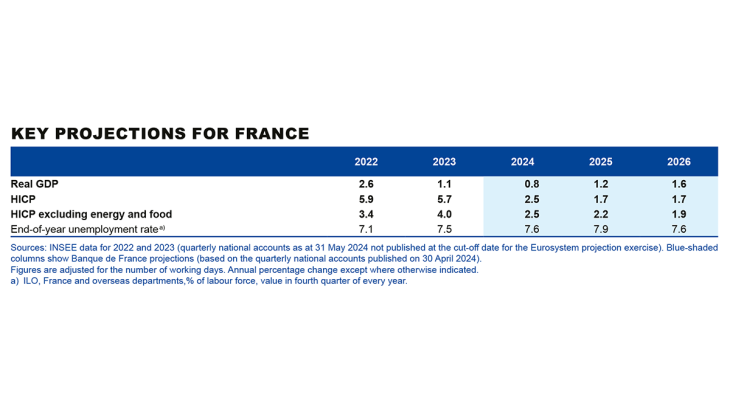

- Our new macroeconomic projections were finalised on 22 May 2024. Our baseline scenario remains that of a gradual exit from inflation without a recession, which should allow for a more marked recovery in 2025 and 2026.

- On the whole, the uncertainties surrounding this baseline scenario remain high and are balanced for economic growth and for inflation. As usual, we have adopted a no-policy-change assumption

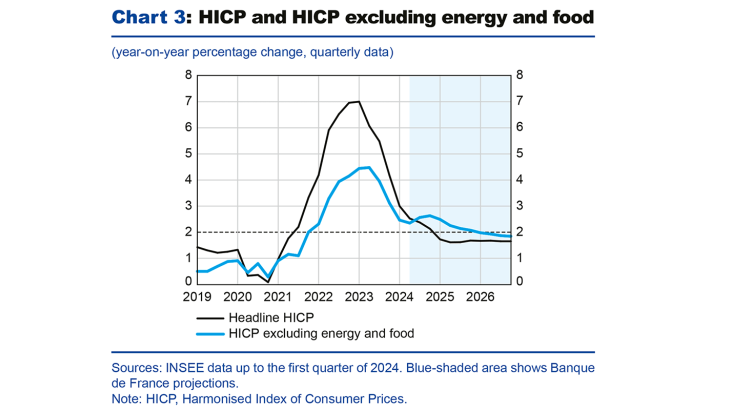

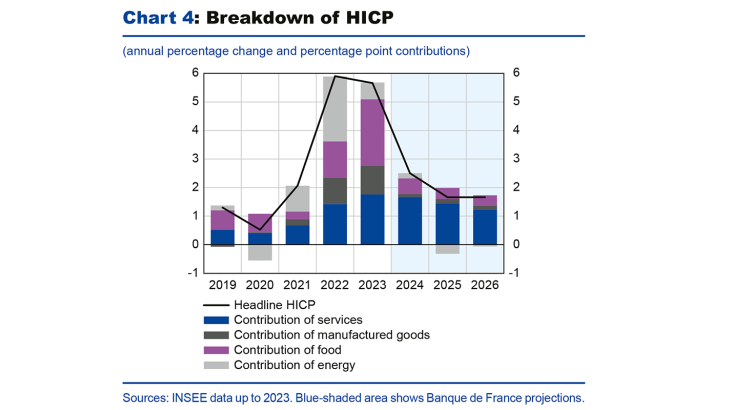

- After still reaching 5.7% in annual average terms in 2023, inflation is set to fall sharply to an annual average of 2.5% in 2024, followed by 1.7% in 2025 and 2026, due to lower inflation for food, energy and manufactured goods. Services inflation is expected to fall more slowly.

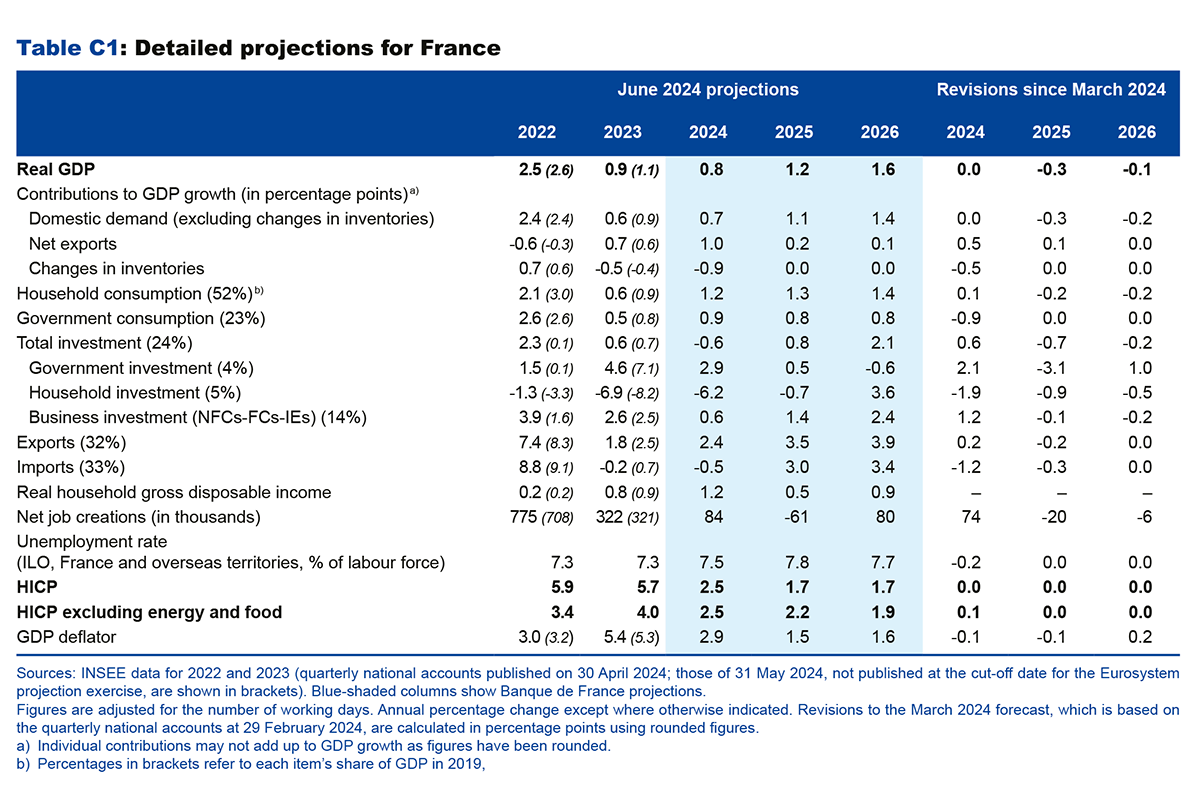

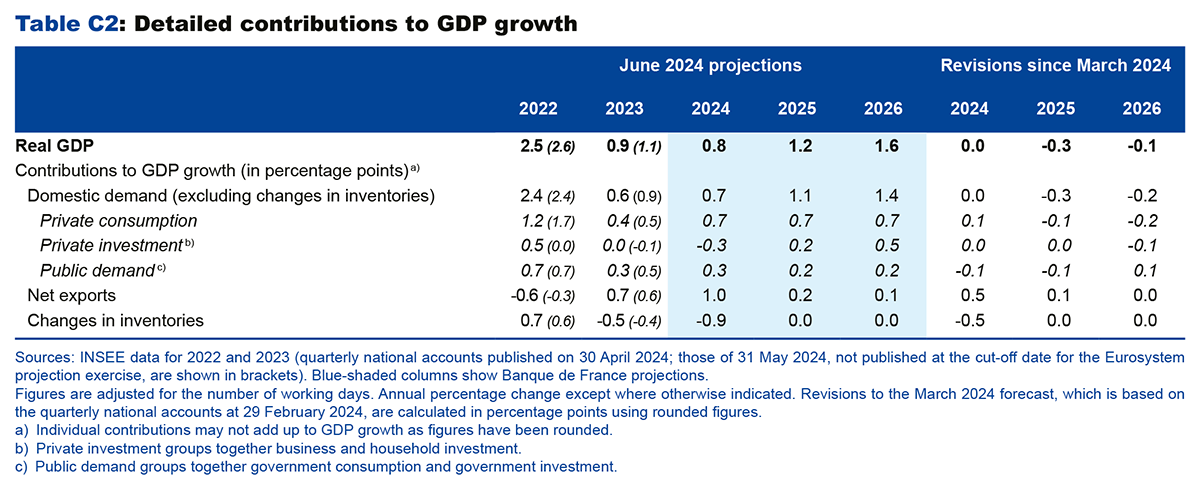

- Economic activity is expected to continue to grow at a moderate pace in 2024, by 0.8%. However, household consumption should benefit from the recovery in purchasing power driven by the fall in inflation. In 2025 and 2026, growth should therefore strengthen to 1.2% and 1.6%, respectively, also buoyed by the recovery in private investment as interest rates ease.

- This forecast is based on the assumption of a significant reduction in the government deficit, to around 4% of GDP in 2026. In any case, the upcoming period of gradual recovery and monetary easing is not unfavourable to the necessary fiscal consolidation needed to bring public debt under control.

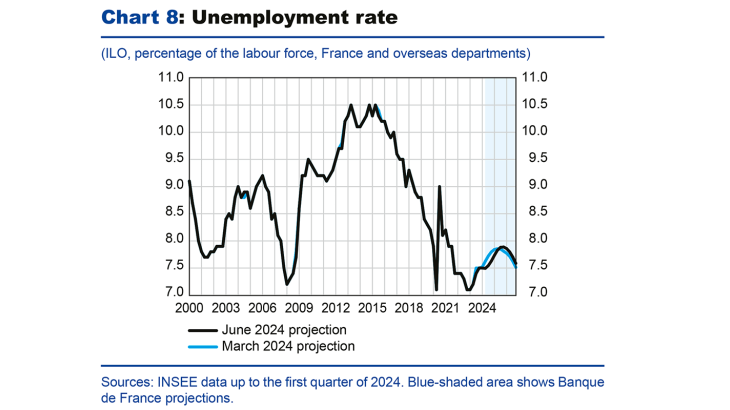

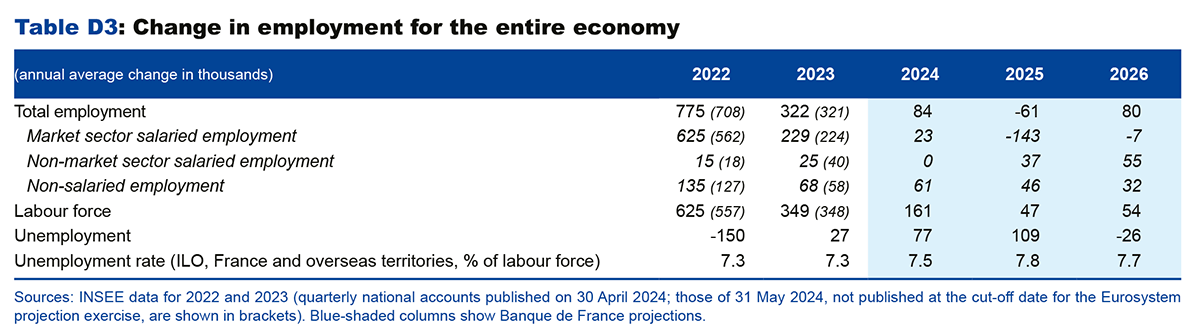

- We continue to forecast a lagged adjustment of employment to the economic slowdown, with only a partial recovery of past productivity losses noted since the pre-Covid period. Consequently, the unemployment rate, which is lower than initially forecast in 2024, is expected to rise temporarily in 2025, before coming down again in the wake of the upturn in activity to stand at 7.6% at end-2026.

Activity should remain slow in 2024, before a recovery in 2025, which should be confirmed in 2026

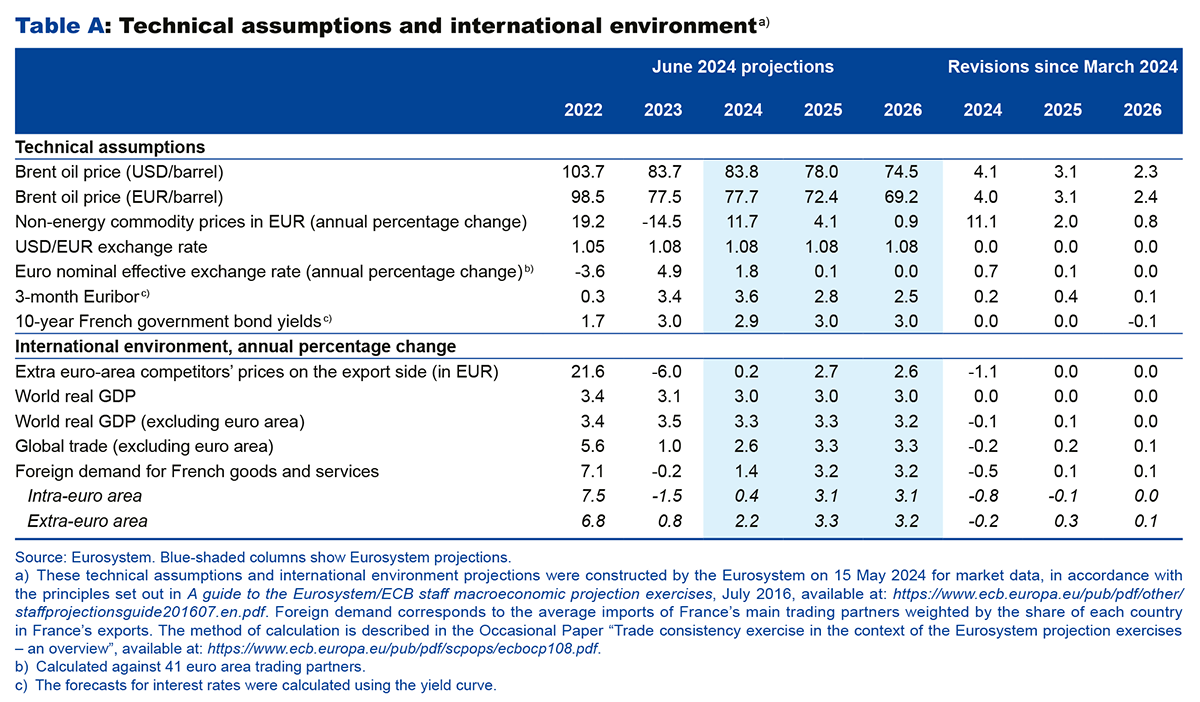

These projections were finalised on 22 May 2024 and incorporate the first estimate of the first quarter 2024 national accounts published on 30 April 2024. They also incorporate final HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) inflation figures for April, published on 15 May 2024. They are based on Eurosystem technical assumptions, for which the cut-off date is 15 May 2024. They do not take account of the detailed figures for the first quarter of 2024 and the annual national accounts published on 31 May and revised for the switch to the new 2020 base (see box for the main implications of these new figures for our projections), and especially not the latest political developments in France.

Economic activity improved at the start of 2024, with growth of 0.2% in the first quarter, in line with the Banque de France's previous Monthly Business Surveys (MBS) and it is expected to be nearly stable in the second quarter, according to the most recent survey at the beginning of June.

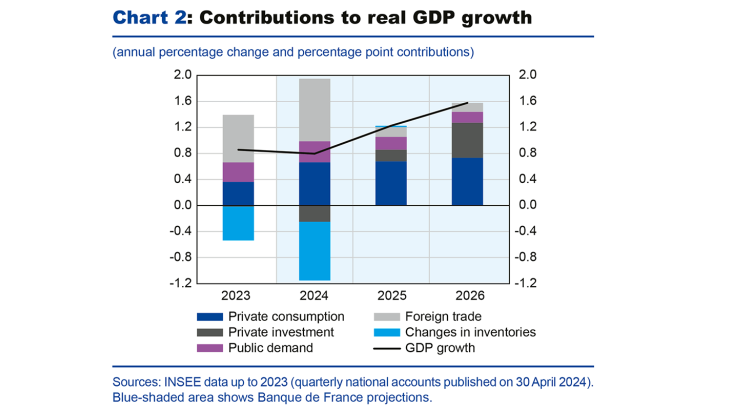

In annual average terms, growth is expected to be 0.8% in 2024. Information published after the cut-off date of 22 May does not lead to any change in the growth forecast for 2024. The most recent quarterly accounts suggest a favourable revision of growth carry-over for the first quarter of 2024, however this is expected to be offset by less favourable growth in the second quarter according to the latest MBS. Growth should be driven mainly by household consumption (see Chart 2), which should outpace GDP growth. Falling inflation should benefit household purchasing power and hence consumption, while the savings rate should remain at a very high level. However, we expect domestic demand to be slowed by business and household investment, which should continue to be held back by financing conditions, as well as by significant destocking. Foreign trade is expected to contribute positively to growth, despite the fact that foreign demand for French goods and services has not yet returned to its trend rate. It should benefit from strong export momentum, sustained by a partial and gradual recovery of market share, especially in the aeronautics sector.

In 2025, GDP growth should accelerate to 1.2%, thanks to a more marked recovery in domestic demand. Household consumption should benefit from the beginning of a fall in the household saving ratio. The contribution of private investment should turn positive once again as the effects of past tightening of monetary and financial conditions begin to subside. The contribution of foreign trade to growth should still be positive, but smaller than in 2024 due to a normalisation of imports after a period of marked decline.

In 2026, the recovery in activity should be confirmed, with GDP growth of 1.6%. Private investment is expected to increase at an even faster pace, thanks in particular to the recovery in household investment. Consumption should continue to grow at the same rate as in 2025, while the saving ratio should continue its gradual normalisation.

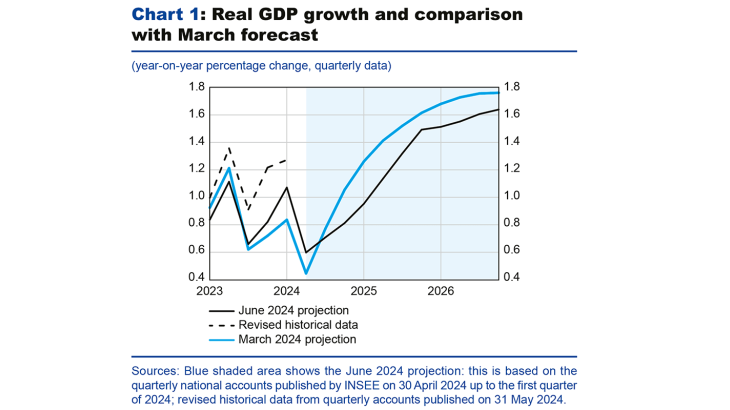

Compared with our previous projection in March, GDP growth remains unchanged for 2024. However, it has been revised downwards by 0.3 percentage point in 2025, and by 0.1 percentage point in 2026 (see Chart 1 above). We have factored in new information that is generally unfavourable to growth. Overall, the revision of the Eurosystem technical assumptions relative to March (based on market expectations in mid-May) has had a downward effect on growth, due in particular to upward revisions to the euro nominal effective exchange rate and energy prices. As the Eurosystem's assumptions were closed off before the fall in oil prices observed since the end of May, this could not be incorporated into our technical assumptions. The projection also incorporates additional fiscal consolidation measures following the publication of the French government's Stability Programme (see the section on public finances). However, these revisions are offset in 2024 by higher growth carry-over for the first quarter than expected in March.

Inflation should fall back towards 2% by early 2025, albeit with fluctuations in energy prices and a slower fall in core inflation

In May 2024, HICP inflation stood at 2.7% year-on-year, up from 2.4% in April 2024. Core inflation (i.e. excluding energy and food) was 2.4% year-on-year in May 2024, up from 2.3% in April 2024. This slight rise in core inflation is due to the price of manufactured goods. Headline inflation has been reinforced by an increase in the year-on-year rise in energy prices, which is the mechanical consequence of the sharp fall in oil prices a year ago.

For 2024 as a whole, the monthly profile of inflation is expected to be affected by fluctuations linked to base effects from movements in energy prices observed in 2023. Aside from these fluctuations, inflation is generally expected to trend downwards, falling from 3.0% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2024, to 2.1% in the fourth quarter of 2024 (see Chart 3). This downward trend should mainly be driven by a marked drop in food and energy inflation (see Chart 4). However, core inflation is likely to be more persistent, even rising slightly over the course of the year to 2.6% in the final quarter of 2024, mainly due to communication services, where prices fell sharply in 2023, but also to rents, because of their indexation to the previous year's high inflation and the end of their capping in April 2024. Core inflation should continue to be dominated by services, due to the delayed impact of wage rises and an improvement in margins in certain sub-sectors. Moreover, we continue to factor in the inflationary impact of geopolitical tensions in the Red Sea on manufactured goods (due to higher transport costs). On an annual average basis, core inflation should therefore be 2.5%, a slight upward revision on the March projection. However, this is expected to be offset by a downward revision in food inflation, so that our headline inflation forecast remains unchanged at 2.5% for 2024 in annual average terms.

Inflation is forecast to fall back below the 2% threshold in early 2025, before retreating over the course of the year, mainly due to the slowdown in services inflation, which should come back to a rate more in line with the wage increases expected after a phase of margin rebuilding in certain sub-sectors. For the year as a whole, the projection has not been revised and remains at 1.7% for headline inflation and 2.2% for inflation excluding energy and food: the slight upward revisions to services and manufactured goods inflation are offset by downward trends in our technical assumptions regarding oil prices (taken from price expectations on futures markets, see Table A in the appendix).

In 2026 – as in our March forecast – we expect headline inflation to remain stable at 1.7%, and inflation excluding energy and food to fall to 1.9%. Services inflation should continue to slow and return, like wages, to a rate closer to that witnessed during the 2000s rather than the period of low inflation in the 2010s.

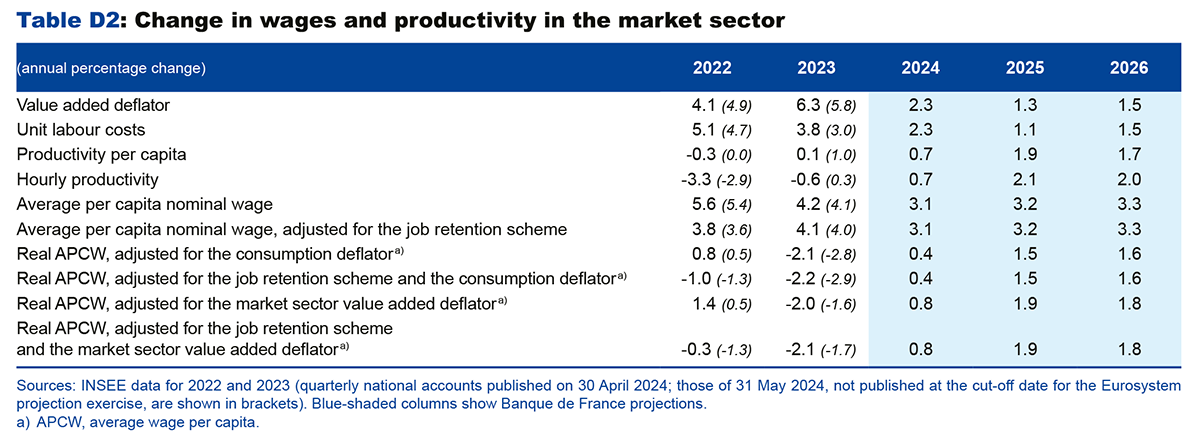

Nominal wages have been slowing, but have grown by more than prices since early 2024

Wages, which have not been growing as fast as prices in recent years, began to slow down from the second half of 2023. In particular, payments of the prime de partage de la valeur (PPV – value-sharing bonus) have been lower than expected, so the average per capita wage increase at the end of 2023 was less than the increase in the monthly base wage, which excludes bonuses and overtime (see Chart 5).

Based on the most recent information available, wages are expected to grow at a rate of close to 3% year-on-year over the coming quarters. Moreover, most wage bargaining has been finalised for 2024, and according to the Banque de France's indicator, based on pay scale increases in over 350 industries, negotiated wages are expected to have risen by 3.5% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2024 (compared with 5.1% in the same period a year earlier). This rate is slightly higher than that of average per capita wages, as it is not impacted by the recent trends in bonuses. The wage forecast also includes an anticipated upward revision of the national minimum wage in the third quarter of 2024, which should however result in a more limited average annual increase in 2024 than in 2023. We also expect lower PPV payments, which are no longer exempt from income tax for most employees.

Nominal wages should continue to rise in 2025-2026, driven by productivity gains and the rebound in activity, despite weaker consumer price inflation than in 2024.

As in our previous projections, nominal wages are therefore expected to increase by more than prices from 2024 on (see Chart 6 above). This should sustain household purchasing power over the 2024-26 period in spite of a downward adjustment in employment in 2025 (see below).

The unemployment rate is expected to post a limited rise in 2025 before falling back in 2026

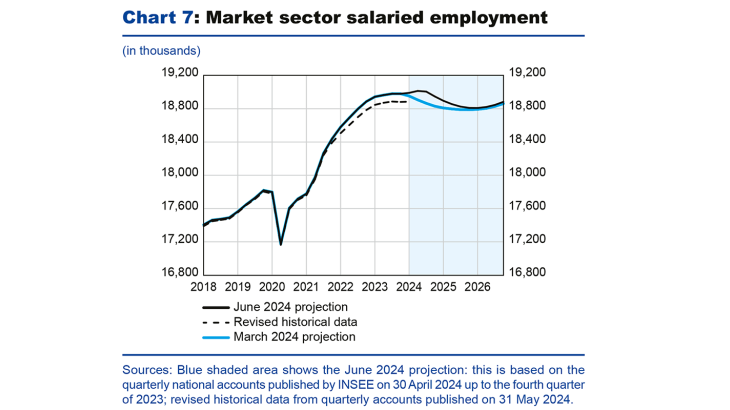

After slowing sharply in 2023, salaried employment in the market sectors picked up slightly in the first quarter of 2024. We expect employment to rise again in the second quarter of 2024, owing to the employment climate as measured by the INSEE business survey. The latter has seen a slight upturn since February 2024, despite an overall downward trend throughout 2023. Compared to our March projection, these latest figures have led us to revise our short-term employment forecast upwards (see Chart 7), and thus to delay the labour market turnaround that we had previously expected to occur from the start of 2024.

Employment is expected to fall from the third quarter of 2024 until the end of 2025. It should be impacted with a delay by the activity slowdown and by the partial recovery in the productivity losses observed since the Covid crisis. Productivity in the market sector has recorded significant losses compared with its pre-Covid trend (see Devulder et al., 2024, Banque de France Bulletin). Over the projection horizon, the gradual end of the labour hoarding observed in certain sectors, such as transport equipment, should contribute to a rebound in productivity gains. However, as most of the productivity losses can be explained by more lasting factors (past increases in apprenticeship contracts and other labour composition effects), this catch-up should only be partial. As a result of the upward surprise in employment at the start of 2024, we have revised our short-term productivity forecast downwards and now expect the partial recovery of productivity losses to occur during the period of strongest growth, in 2025-26.

Our employment projection also takes into account the expected effects of the reform of the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA), which makes receipt of the benefit conditional on the completion of at least 15 hours of work per week. This reform should lead to a rise in the labour force, with a small upward effect on the unemployment rate in the short term (the time it takes for new entrants to the labour market to actually find a job), but a slight positive effect on employment and activity in the medium term (of around 0.1% in both cases).

Given the new employment (see Chart 7 above) and labour force trajectories that we are forecasting, the rise in the unemployment rate is delayed relative to our March publication (see Chart 8 above). It should peak at 7.9% at the end of 2025, before dropping again in 2026 as a result of the acceleration in activity.

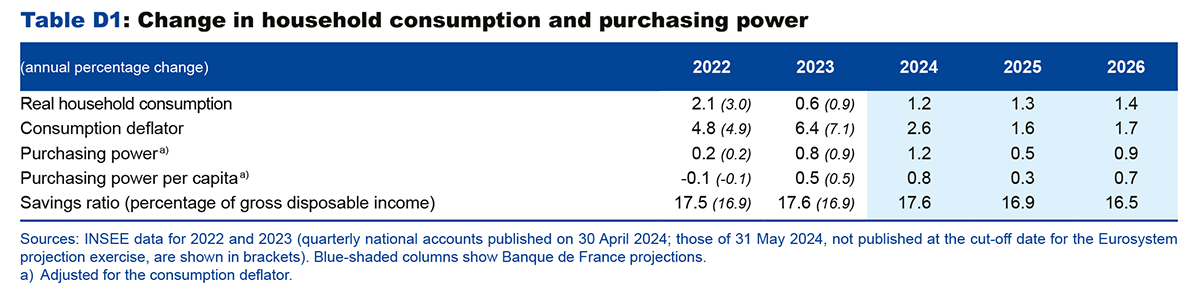

Household consumption should once again be the main driver of growth from 2024, buoyed by purchasing power gains and a partial decline in the saving ratio

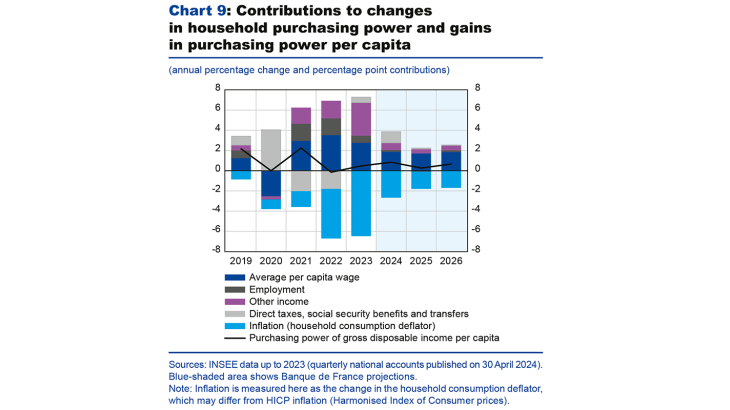

In 2023, the purchasing power of household disposable income rose by just under 1%. This change in households’ real income is an average that includes all income items (including property income, income stemming from job creation, and social transfers); it may therefore differ from individual households’ own perceptions of their finances. In 2023, household income was thus supported by continuing strong job creations and high social transfers, but even more so by the rise in income from assets, which offset the fall in per capita real wages. In 2024, growth in household purchasing power (1.2%) is expected to strengthen, thanks to an increase in real wages, the impact of which should be mitigated by a smaller contribution from other income items (see Chart 9). In 2025, growth in purchasing power is expected to slow (0.5%). This slowdown can be explained by the adjustment in employment, slower growth in other income items, in particular property income, and smaller increases in social transfers as a result of measures to control public spending. In 2026, growth in purchasing power is expected to pick up (0.9%) thanks to the recovery in employment.

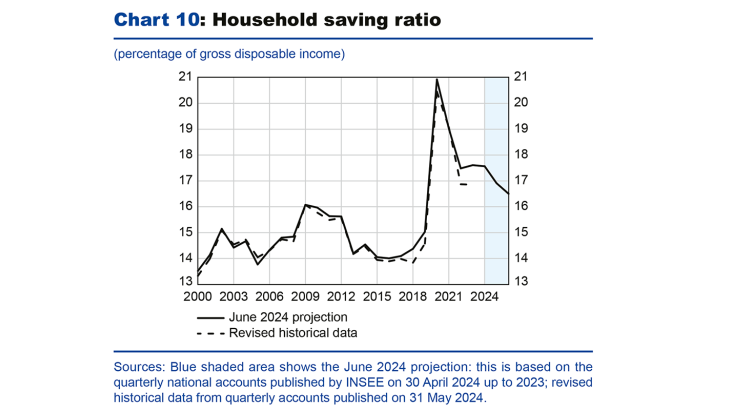

This increase in households’ purchasing power should support their consumption over the projection horizon: it is expected to rise by 1.2% in 2024, 1.3% in 2025 and 1.4% in 2026. Consumption should also benefit from a very gradual fall in the saving ratio from 2025 onwards. The saving ratio in the first quarter of 2024 is around 3 percentage points higher than its historical pre-Covid average. This still high level could partly stem from the need for households to save more to offset the decline in value of their assets through inflation, which should diminish in the future as inflation recedes. Overall, the saving ratio is expected to decline over our projection horizon, but should remain above its pre-Covid average in 2026 (see Chart 10 above).

Household investment contracted sharply in 2023, but initial indicators now point to a future recovery. Firstly, households' real estate purchasing power has improved, even if the market is still taking a wait-and-see attitude. Secondly, new loans to households picked up in April. Finally, building permits and housing starts appear to have stabilised after a long period of decline. Given the usual lag of around a year between housing starts and construction, we expect the contraction to be less severe in the coming quarters, with a recovery starting in 2025. Household investment should pick up more markedly in 2026, when the effects of the past tightening of monetary and financial conditions have faded and households’ real estate purchasing power has sufficiently recovered.

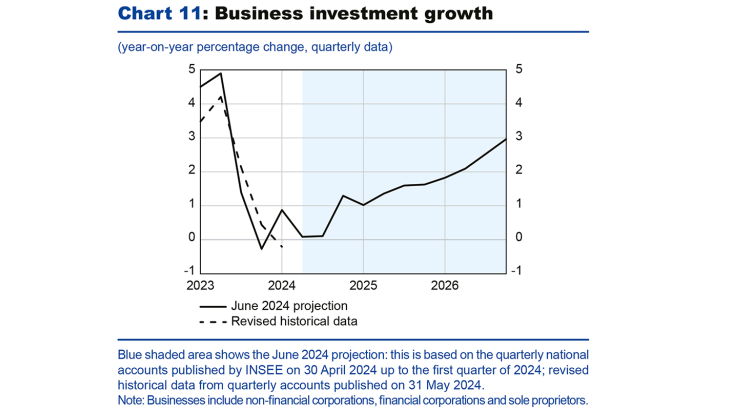

Business investment should continue to slow in 2024, before picking up in 2025-26, boosted by the recovery in activity and the gradual easing of interest rates

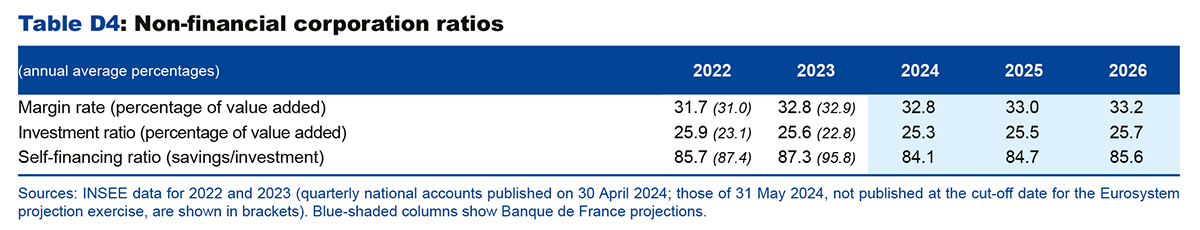

In 2024, business investment is likely to be penalised by relatively sluggish activity, as well as by financing costs and lending conditions. However, bank interest rates for businesses have started to decline slightly, and according to the latest results of the Bank Lending Survey (BLS), lending conditions are no longer tightening. As a result, business investment growth is likely to bottom out until mid-2024, before picking up again in 2025-26 (see Chart 11). In the future, it should be underpinned by investment in the digital and energy transitions, as evidenced by the announcements of investment in electric battery “gigafactories”. The recovery in investment should also be supported by the upturn in activity and by continued high corporate margins.

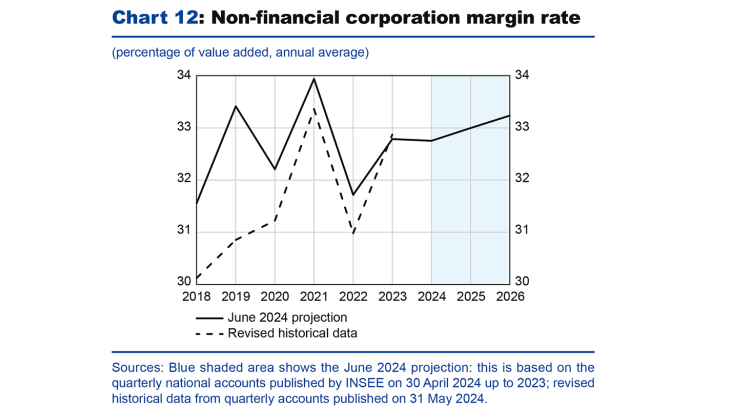

Due to the recovery in productivity gains, growth in unit labour costs in the market sector is expected to slow, slipping from 2.3% in 2024 to 1.5% in 2026. Against a backdrop of limited growth in the non-financial corporation margin rate (0.5 percentage points between 2023 and 2026, see Chart 12), this slowdown should lead market sector industries to record lower price rises: growth in the market sector value added deflator should thus be 1.5% in 2026.

Based on our conventional consolidation assumptions, the government deficit should fall towards 4% in 2026

In 2023, the government balance deteriorated, falling to -5.5% of GDP after -4.8% in 2022. This surprise on the downside is mainly attributable to lower-than-expected taxes and social security contributions at the end of the year, with declines in corporation tax and real estate transfer taxes in particular. After posting very strong growth for two years, tax receipts lost momentum and increased less strongly than economic activity.

In 2024, spontaneous growth in taxes and social security contributions should remain slightly lower than that of GDP, before normalising in 2025-26. Government expenditure is expected to grow only slightly in 2024, as a result of the withdrawal of exceptional measures taken to deal with the energy crisis and the savings contained in the decree cancelling budgeted spending on 22 February.

The strictly conventional assumptions adopted regarding projected budgetary savings (by reference to the average annual growth rate of government expenditure over the previous decade) would imply a primary structural adjustment of 0.6 potential GDP points in 2025 and 2026, which is higher than the minimum adjustment of 0.5 GDP points required in the event of an excessive deficit procedure under the new European budgetary rules. However, the adjustment taken into account is smaller than that planned in the Stability Programme (1.2 GDP points in 2025, then 0.5 GDP points in 2026), which is based on savings that have not yet been detailed.

Under our assumptions, the government balance should be -5.2% in 2024, dropping to -4.8% in 2025 and reaching -4.1% in 2026. Fiscal consolidation is needed to bring the public debt under control.

The risks to our baseline scenario are on the whole balanced for activity and inflation

Even more so than in our previous projections, the political context remains highly uncertain, due in particular to the recent developments in France and to geopolitical factors: the war in Ukraine and the situation in the Middle East. A worsening of these tensions could have an impact on oil and gas prices, maritime transport costs, global demand and uncertainty levels. This would pose an upside risk to inflation and a downside risk to economic activity. It should be noted, however, that oil prices have dropped sharply since the end of May, and are now well below the assumptions adopted in this projection. Still at the global level, there is also an upside risk to demand from the United States, which could turn out to be greater than in our baseline scenario, particularly in the event of prolonged fiscal expansion. Conversely, increased fragmentation of global trade could weigh on foreign demand for French goods and services.

At the domestic level, the risks to household consumption and business investment are balanced. On the one hand, we project only a partial return of the saving ratio towards its pre-Covid level by 2026. The saving ratio could decrease more rapidly, or conversely remain persistently high. On the other hand, firms will face a rising interest burden as they renew their loans at higher rates than in the past, which could generate a downside risk to our investment scenario. Conversely, thanks to their high margins, firms could invest more than expected to meet the major needs associated with the ecological and digital transitions.

The fiscal adjustment measures represent another risk to our GDP growth projection for 2025-26. In the absence of precise specifications of the measures contained in the Stability Programme, we have in fact adopted a lower strictly conventional adjustment assumption than that set out in the programme. The scale of the negative impact on growth of aligning the primary structural adjustment with that of the Stability Programme is uncertain: its estimate depends very much on the composition of the measures implemented, which may have different fiscal multipliers (effect on growth of a fiscal measure).

In addition to the geopolitical risks mentioned above, there are two specific downside and upside risks to inflation. On the one hand, the slowdown in nominal wages was more pronounced than expected at the start of 2024 and it could continue to be more marked than in our baseline scenario, which could reinforce the slowdown in services prices. On the other, we cannot rule out the possibility of another downward surprise on business productivity, which could reinforce the dynamics of unit wage costs and give rise to additional inflationary pressure.

Finally, the staging of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Paris should lead to a rise in demand for certain goods and services, owing to the movement of athletes and sports delegations and the influx of tourists attending the competition. As the sectors concerned are mainly accommodation and food services and transport in the Île-de-France region, and for a short period only, we expect the upward impact on inflation and economic activity to be only limited in our baseline scenario. However, the scale of these increases remains uncertain and constitutes a risk to our projections.

Box

Open box

On 31 May 2024, INSEE published the second estimate (detailed figures) of the national accounts for the first quarter of 2024, which includes the switch to a 2020 base. Because of the cut-off date for the macroeconomic projection exercise, it has not been possible to take these figures into account.

GDP growth for the first quarter of 2024 has been confirmed at 0.2%, while annual growth for 2023 has been revised upwards to 1.1%, instead of 0.9% in the first estimate of the quarterly national accounts published on 30 April (see Chart 1). However, the composition of first-quarter 2024 growth has been revised relative to the first estimate. Domestic demand made a positive contribution (+0.1 percentage point, pp) to growth over the quarter, but has been revised downwards by 0.3 pp compared with the first estimate, mainly due to the downward revision to household consumption growth (to +0.1%, from +0.4% in the first estimate). Conversely, the positive contribution of foreign trade to growth has been revised upwards to 0.2 pp (compared to 0.0 pp in the first estimate), due to a more marked increase in exports than in imports. Lastly, the contribution of inventories to growth remains unchanged (-0.2 pp, as was the case in the first estimate).

As regards households, the saving ratio has been revised downwards over the long term (see Chart 10), mainly due to a revision of consumption momentum since 2021, but it rebounded in the first quarter of 2024 to reach the level expected in our forecast. The saving ratio therefore remained significantly higher than its pre-Covid level. The new data available does therefore not challenge our forecast of a partial and gradual fall in the saving ratio, which would help support household consumption.

For businesses, the margin rate has been revised only slightly for 2023 (32.9% compared with 32.8% in the first estimate, see Chart 12). However, it has been revised downwards in past data, leading to an upward trend since 2018, when it was revised downward by -1.5 pp. In the first quarter of 2024, it stands at a much lower level than expected (32.1%, compared with 32.9%). This drop, which is more marked than that in our forecast (-0.1 pp), reflects the sharp downward revision to growth in the market sector value added price (-0.5% versus +0.6% in the first estimate). If this first quarter variance were to be maintained in the forecast, this would lead us to forecast a margin rate of around 32.5% in 2026 (instead of 33.2%), a level approximately 1.5 points above the 2019 level (30.9%), which can now be used as a pre-Covid benchmark year, no longer impacted by the double-counting of the crédit d’impôt pour la compétitivité et l’emploi (CICE – tax credit for competitiveness and employment) at the new base. This trend would appear to be compatible with the scale of cuts in production taxes (net of subsidies) that took place over this period. The business investment ratio has a less pronounced upward trend in the new accounts, which may suggest a less positive investment dynamic in the future.

Finally, per capita productivity in market sectors has deteriorated by less since 2019, due to a downward revision of employment (see Chart 7) combined with an upward revision of value added in volume. The pre-crisis productivity trend has also been significantly revised, to 0.6% per year over the 2010-19 period (compared with 0.7% previously). The loss of per capita productivity in market sector industries, as a deviation from the estimated trend over the pre-Covid period, which was previously estimated in Devulder et al. (2024, Banque de France Bulletin) at 8.5 % in the second quarter of 2023, has been revised to 5.9%. These lower productivity losses represent a downward risk for our per capita productivity forecast, and an upward risk for employment, as they would require fewer productivity gains for their temporary portion to be absorbed over our projection horizon.

Updated on the 5th of September 2024