Post No. 389. We present results from an analytical tool developed at Banque de France that measures the fragmentation of the world economy. The Ukraine war has reinforced a trend to trade relatively more with countries in the same geopolitical bloc and less so with those in opposing blocs. Such a “East-West divide” can be traced back to the US-China trade war of 2018.

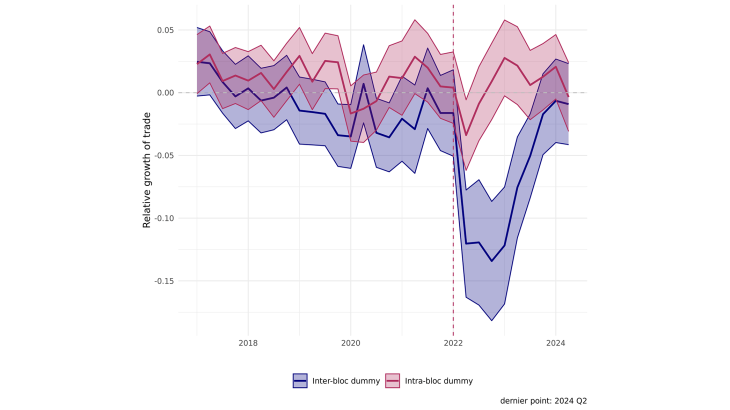

Figure 1: The Fragmentation of World Trade according to geopolitical blocs

Note: The red line shows bilateral trade growth deviation between same-bloc countries from trade growth with neutral countries); the blue line shows trade growth deviation between opposing-blocs countries from trade growth with neutral countries.

The idea that the world has entered a new era of globalization is gaining ground. In particular, the notion of a fragmenting world economy where trade flows between geopolitical blocs composed of like-minded trade partners is rising at the expenses of trade between countries in rival blocs (IMF, 2024). These movements are underlined by policies aimed at shaping trade relations for strategic and economic security considerations, such as subsidies conditioned on the origin of critical materials or economic sanctions motivated by military conflicts. Businesses react to the new context by reshuffling their global supply chain operations. Analysts of the global economy - among which central banks and other policy institutions - are faced with the increasing need to monitor the extent of such fragmentation.

In this post, we present the results obtained from an analytical tool developed at Banque de France that serves such a purpose. Using detailed international trade data starting in 2017 we track the effect of geopolitical alignment on trade flows. We allocate countries intro three geopolitical blocs: the “West”, the “East” and “Neutral”, using their positioning in UN resolution regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and other criteria in the geopolitical index by den Besten et al. (2023), such as the number of times the country received sanctions from one bloc, the origin of military imports and the participation in China's Belt and Road Initiative. We use bilateral trade data at product-country level for 57 declaring countries. We apply an econometric strategy - the estimation of “gravity” equations - that allows isolating the effect of geopolitics by purging other well-known determinants of international trade flows, such as distance or the size of trading partners, while controlling for product-specific shocks (for example, energy-related price shocks). More specifically, for each quarter, the year-on-year variation in log exports of granular trade flows (e.g. an exporter shipping a good to an importer) is regressed on 'gravity' variables (e.g., distance, contiguity, common language), a set of fixed effects capturing non-bilateral changes such as country-product price developments, and inter-bloc and intra-bloc dummies. The coefficients of these dummies are then collected and plotted.

A strong reallocation of trade flows towards “friendly” countries is visible since the invasion of Ukraine

The sharp fall of the blue line (“inter-bloc” trade) indicates a strong negative effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on trade between countries pertaining to antagonistic geopolitical blocs, with respect to trade with neutral countries (Figure 1). At its peak in the third quarter of 2022, this reallocation effect implied that the value of trade between non-aligned countries decreased by 15% with respect to the same quarter of 2021. At the same time, trade between “friendly” countries (“intra-bloc” trade) showed a milder increase of around 5% with respect to trade with neutral countries. The difference between the two curves shows a differential growth rate close to 20% favoring trade with friends at the expense of trade with non-aligned countries. In non-reported analyses we find that the effects are mostly driven by trade in goods in the category Parts and Components, showing that “friendshoring”, the strategy to offshore to countries with similar political views, is gaining ground within global value chains.

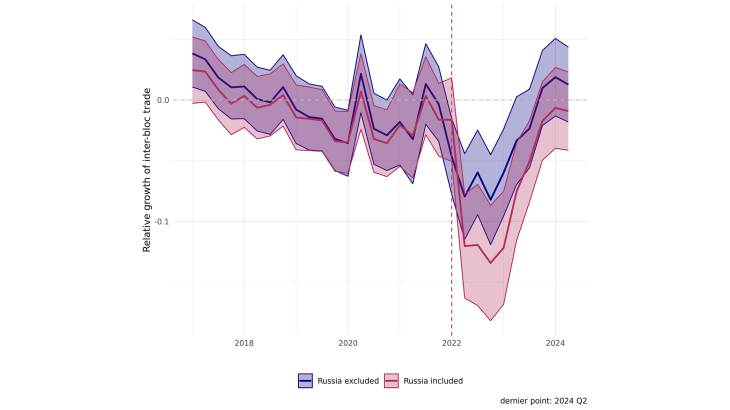

The trend towards friendshoring goes well beyond Western sanctions to Russia

The invasion of Ukraine prompted Western countries to introduce a wide number of sanctions against Russia as part of an economic warfare strategy. These included policies that restricted trade with Russia directly, such as export restrictions, imports bans and caps on the price of Russian oil, as well as measures that affect trade indirectly, for example cutting Russian banks from the international payments system. Our analysis show that fragmentation generated by the Russo-Ukraine war goes well beyond the direct effects of cutting ties to Russia. In Figure 2 we repeat the exercise but separating Russia from the rest of the Eastern bloc, in the blue line. The distance between the two lines shows that the effect of sanctions is very important and accounts for a large share of the reallocations. However, excluding Russia from the estimations still shows a significant decrease in inter-bloc trade flows. Fragmentation is a deep structural feature of the world economy.

Figure 2: An effect that goes beyond sanctions to Russia

Note: Both lines show the evolution of trade growth between countries in opposing blocs (relative to trade with neutral countries). The red line includes Russia both as importer and exporter.

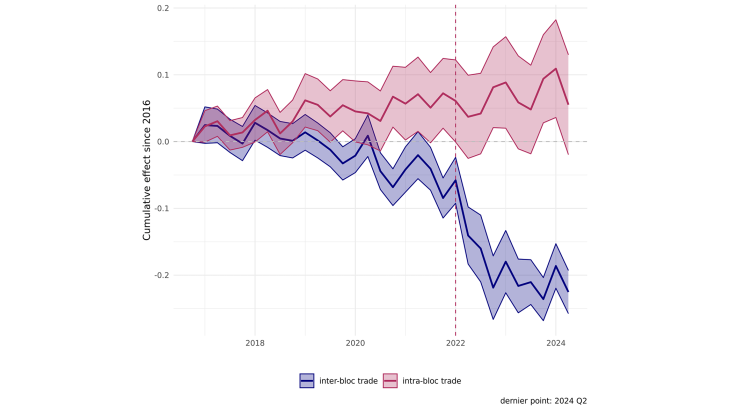

A structural trend towards fragmentation that started around 2018

Looking at a longer period starting in 2017, the trend towards fragmentation of international trade appears to start some years before the Ukraine war. In Figure 3 we use our estimations to plot the evolution of an index that tracks the growth of inter- and intra-bloc trade, measured with respect to trade with neutral countries, as above. The index takes the value 100 in the first quarter or 2017. Each point measures the cumulated growth at each point in time with respect to this starting date. In the last quarter of 2023, inter-bloc trade was 25% lower than in 2017, whereas intra-bloc trade grew 15%, pointing to a deep change in the structure of the global economy.

Most importantly, fragmentation began to have some bite in the first quarter of 2018, at a time when the US and China, big players of the West and East blocs respectively, engaged in a trade war by raising bilateral tariffs significantly for a large range of products. Interestingly, the trends towards fragmentation paused briefly during the Pandemic, when West was faced with the need to import from China. Under this longer view, the effect of the Ukraine war was to enhance a previously-engaged trend towards an East-West divide in world trade flows.

Figure 3: The trend towards trade fragmentation starts in 2018.

Note: The figure shows a log index (base 0 in 2017Q1) tracking cumulative trade growth relative to trade with neutral countries over time. The blue line reflects the inter-bloc dummy, and the red line reflects the intra-bloc dummy from Figure 1.

Our analysis, using detailed bilateral trade data unveils a clear trend towards the fragmentation of the international trading system. Global economy analysts are therefore faced with the need to update their toolkit to properly monitor the evolution of a fragmenting world economy. Our work is a step forward in that direction.

Download the full publication

Updated on the 14th of February 2025