Do SLBs really improve corporates' climate performance?

Economic actors must adapt to climate change, which implies a commitment to decarbonise their activities. With this in mind, the climate performance of companies can be defined by their volume of GHG emissions and/or by their commitment to a GHG reduction trajectory. Emissions are classified by scope: Scope 1 covers a company's direct emissions from sources it owns or controls. Scope 2 covers emissions resulting from a company's use of electricity, heat or steam. Scope 3 covers other indirect emissions, upstream or downstream of the production cycle. Not all economic activities are equally affected by this need for adaptation and some sectors have to make significant efforts to achieve it. The lack of adaptation generates financial risks over time (Boissinot, Clerc and Dees, 2021).

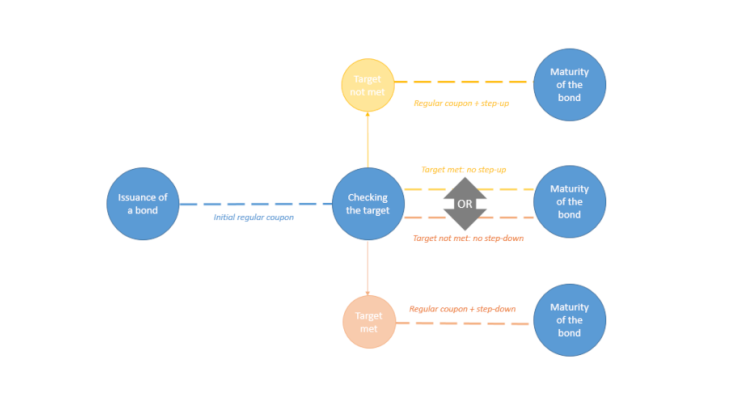

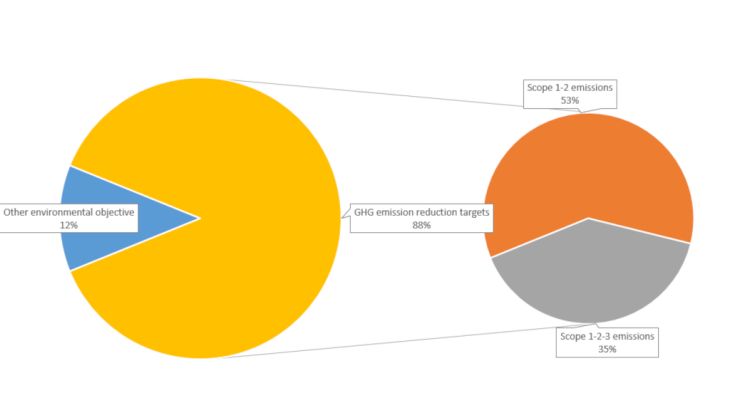

In this matter, the environmentally-targeted SLB mechanism signals the commitment of the issuer to reduce its GHG emissions, by linking it to financial commitments. However, the relevance and ambition of the targets are difficult to assess and the level of financial penalties for not meeting the targets is generally low. For example, indirect GHG emissions (Scope 3) are sometimes missing from the climate targets of SLB issuers in sectors where Scope 3 emissions are significant. In addition, the most common level of SLB step-up (i.e. premium to be paid to investors in the event of missing the target) averages 25 basis points (0.25%), compared to 125 basis points (1.25%) for a step-up linked to the change in the issuer's credit rating, which is common in the market. Lastly, any early repayment clause weakens the constraint created by the mechanism (Kölbel and Lambillon, 2022).

Against this backdrop, the ESG markets do not values SLBs in the same way. Most SLBs do not seem to have a significant premium (equivalent to a “greenium” for green bonds) over conventional bonds (Mirova 2022). SLB issues with a higher level of step-up or step-down nevertheless seem to benefit from a premium from investors (Kölbel and Lambillon, 2022). SLBs exist in a variety of forms and are sometimes difficult to value on the markets, as they are the result of tailor-made choices made by each issuer.

To address these limitations, the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) recently listed 300 standardised ESG targets for SLBs, by sector of activity. The ICMA provides benchmarks for issuers to calibrate their targets and recommends adopting targets based on Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions for most sectors. In addition, the European Commission announced in July 2021 its plans to develop a label for SLBs. These initiatives are likely to consolidate issuances in the SLB format and to improve target relevance assessment over time.

For the most polluting sectors, the European project to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 creates more effective decarbonisation mechanisms, notably with emission quotas and carbon markets to which applies to a growing number of economic actors. In this respect, the choice of the SLB format to issue debt is an additional sign of commitment by corporates to the transition.