Spatial inequality has become a key policy concern across much of the advanced world, prompting a spate of government action on the issue in recent years (see Ottaviano et al. 2013, Barone et al. 2016). If policymakers are to address spatial inequalities, they need good evidence on how spatial inequality has changed over time and how this compares across countries. This paper presents evidence showing that, contrary to the popular narrative, North America and Europe have followed different patterns on spatial inequality, with spatial inequality actually falling in the European countries studied. It highlights that spatial inequality in wages is not a major contributor to national income inequality.

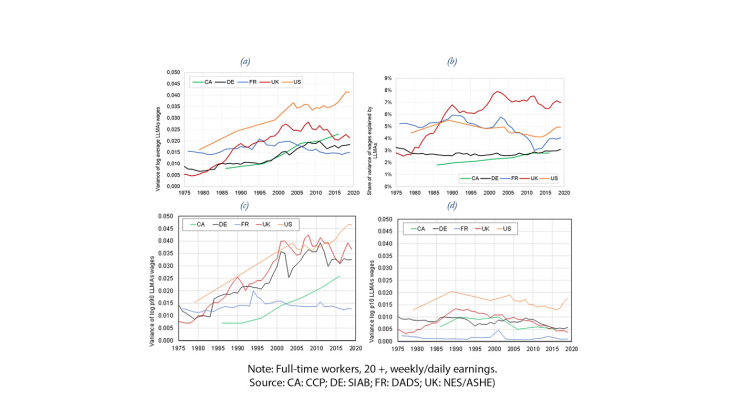

We consider how patterns of spatial inequality have changed since the 1970s to 2020s in five major advanced economies - the United States, Canada, (West) Germany, France, and the UK. Our focus is on primary wages, rather than incomes or productivity. We focus on labour income, reflecting the fact that the lion’s share of rising income inequality comes from this source (Atkinson et al. 2011), and consider pre-tax weekly labour income for full time workers aged 20 or above. Crucially, we use microdata sources to construct wage distributions in comparable local labour market areas across these countries, meaning that the geography we use reflects economic reality not political or administrative boundaries. While some of our findings will be expected, some of what we find challenges the established views. First, as most people would expect, our findings show major differences in spatial inequality across countries. Panel (a) in the Figure below gives the variance of log mean local labour market wage, a measure of inequality between local labour markets. In 2016, the last year we have data for all countries, the US is most unequal by this measure, followed by Canada, the UK, Germany and France. But the United States is an outlier on this measure – inequalities in the other countries are relatively similar. It is important that we put spatial inequality in other countries in context, and do not read across from the exceptionally high levels of the US.

Now consider the trends in the data. There is a common belief that spatial inequality has been skyrocketing in recent years – but our data challenges this narrative. The US has indeed seen the largest increase in spatial inequality which has dominated the established narrative. In Canada the trends are similar, as there has been a large rise in inequality, but the levels remain far lower. Nevertheless, our three European countries have seen spatial inequality fall. The UK, in particular, has seen spatial wage inequality fall since 2010 (also reported in Overman and Xu 2022). So, while it is right to say that spatial inequality has increased in all countries since the early 1980s, we should not extrapolate this trend. Since the start of the millennium, patterns of inequality have diverged across these five countries and North America has followed a very different pattern to Europe. It is also important to note that these trends are driven almost entirely by the incomes of high-earners. Panels (c) and (d) in Figure below shows wage inequality at the top (log 90th percentile) and bottom (log 10th percentile). While the latter has flattened across all countries (although it is still markedly higher in the US), the former is much more variable. The lowest earners earn similar amounts wherever they are, so that we can conclude that spatial inequality is driven by the geography of the highest earners.

Finally, one important question is how much spatial inequality contributes to national wage inequality. One approach to this it to decompose the total variance in wages into between area and within area components (Gibbons et al. 2014). Our conclusion is that across all countries, inequalities within local labour markets contributes more than inequality between them. As shown in panel (b) in the Figure below, between-area inequality in average wages contributes most to national wage inequality in the UK, with around 7% of total variation in wages explained by the contribution of local labour markets, and least in Canada, (only 3%). The only country which has seen a significant increase in the importance of inequalities across local labour markets, by this measure, is the UK. We also illustrate the extent to which differences in average wages between areas change national wage inequality by conducting a counterfactual exercise. We equalise average wages across local labour markets, and then construct counterfactual series of national wage inequality. Counterfactuals of national wage inequality are very close to the original observed results, consistent with our findings about the variation of wages.

To summarise our results, we show that, by the end of the last decade, spatial inequality in wages were similar in France, Germany, the UK, and Canada, but much higher in the US. Rapid growth in wage inequality in the 1980s and 1990s has abated since the millennium, except in the United States. And inequality by this measure has actually been falling in France which also remains the least spatially unequal country we study. But the inequality in average area wage is not a major contributor to national inequality, contributing only 7% in the UK, the country where place matters most. On the other hand, we see that inequality between areas at the top of the distribution has continued to grow, except in France.

Keywords: Regional Inequality, Wage Inequality, Local Labour Markets

JEL classification: J3, R1, R23