Companies that issue leveraged loans are by definition heavily indebted. This makes them highly vulnerable to an increase in the cost of debt or a reduction in the credit supply, especially in the event of a macroeconomic or financial shock that could potentially increase their risk of default.

The leveraged loan market is also characterised by a strong presence of non-bank investors (CLOs, investment funds, pension funds, insurers, hedge funds). While banks have been urged by regulators to reduce their risk exposure since the financial crisis, non-bank investors have benefited from a less strict regulatory environment, enabling them to increase their share in this market.

Another vulnerability is the reduction of subordinated debt – that is the debt that can absorb losses before more senior tranches – thereby reducing expected recovery rates and thus investor protection.

In addition, a significant share of these loans has not been used to finance productive investment, which would have improved the borrower’s profitability; it has instead been used to finance mergers and acquisitions, share buybacks, or to pay dividends (Adrian et al., 2018).

Subprimes vs leveraged loans: similar but not the same

Concerns about leveraged loans have been fuelled by the apparent similarities with the subprime mortgages that triggered the 2008 crisis:

- deteriorated solvency of the debtor, be it a household or a company;

- strong growth in the securitisation of these speculative loans;

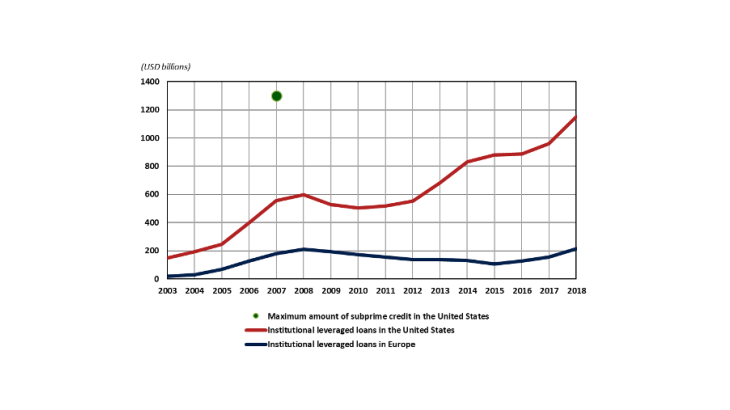

- similar outstanding amounts : USD 1.2 trillion of institutional leveraged loans at end‑2018 (around 12% of total US corporate debt) compared to USD 1.1 trillion of subprime mortgages at end-2006 (around 13% of total mortgage loans).

However, several differences remain:

- Banks appear to be less directly exposed to leveraged loans than they were to the subprimes in 2007-08.

- The collateral is not residential property: leveraged loans offer a larger diversity of sectors. However, if investors came to perceive leveraged loans as a separate, standalone asset class, then the benefit of this sectoral diversification would be lost.

- The securitisation market appears to be smaller: it is estimated that about a third of leveraged loans are securitised, compared to 80% for subprimes in 2007. Furthermore, liquidity risk for CLO is limited, as the maturity of the liabilities is generally longer than the average maturity of the assets.

Although any comparison with the subprime market remains questionable, leveraged loans still pose a number of risks to financial stability. The presence of Exchange Traded Funds and Mutual Funds means that retail investors have access to these loans in the United States – although they still only account for a minority of investors. Moreover, these structures present a maturity mismatch between their assets and their liabilities. Investors can redeem their fund shares very quickly, whereas underlying assets (leveraged loans) tend to have much longer transaction times. In the event of a macroeconomic or financial shock, a widespread deterioration in the credit quality of leveraged loans could trigger a mass sell-off by investors, leading to a fall in prices in the secondary market.

In light of these vulnerabilities, the leveraged loan market could potentially act as an amplifier of a macroeconomic or financial shock in the United States. After the Bank for International Settlements and the International Monetary Fund, the US Fed also raised awareness about this issue, while at the same time considering that leveraged loans do not pose a systemic risk.