In this paper, we identify two counteracting effects of credit access on productivity growth. One the one hand, better access to credit makes it easier for entrepreneurs to innovate, which is the direct effect already emphasized by the existing literature on financial development and innovation-based growth. On the other hand, there is an indirect reallocation effect of credit access on productivity growth: namely, better credit access allows less efficient incumbent firms to remain longer on the market, thereby discouraging entry of new and potentially more efficient innovators. This latter counteracting effect is quite similar to the negative reallocation effect of subsidizing incumbent firms.

In the first part of the paper, we develop a simple model of firm dynamics and innovation-base growth with credit constraints, to formally uncover the direct and indirect effects of credit access on productivity growth. Moreover, the model shows that, under suitable conditions, these two counteracting effects generate an inverted-U relationship between credit access to incumbent firms and productivity growth.

In the second part of the paper we confront our theoretical predictions to the data. We use the FiBEn firm-level database constructed by the Bank of France which provides information on firm size, firm-level production activities, and firms' balance sheet and P&L statements. In addition, we use information on credit access by firms, which we proxy by a rating variable called Cotation which rates firms according to their financial strength and capacity to meet their financial commitments. This Cotation (or rating) measure is considered to be a proxy for credit access, as it is widely used by banks when deciding whether and how much to grant credit to firms, and it is also used by the Eurosystem - in particular the European Central Bank (ECB) - when assessing whether a bank's credit to a particular firm can be pledged as collateral against central bank refinancing, and we indeed show that this rating measure is indeed positively correlated with the firm's credit access (measured by both, the amount of loans the firm gets and the interest rate it faces).

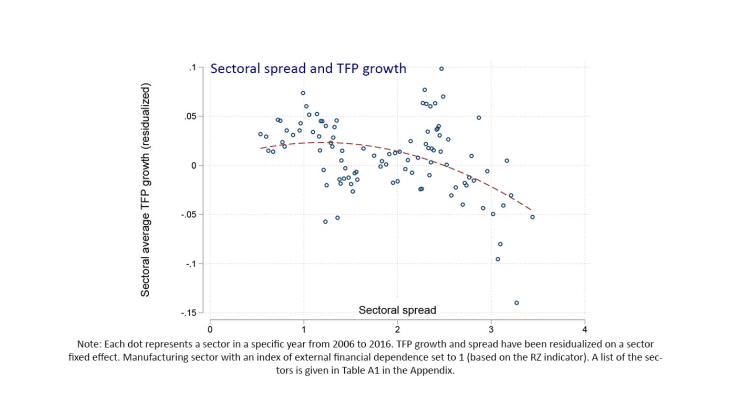

We first perform cross-sector panel analysis. There, we regress sectoral growth on a sectoral measure of credit constraint - namely the difference between the average rate of new loans to firms in the sector and a reference rate, controlling for sector fixed effects. We find evidence of an inverted-U relationship between credit constraints and productivity growth.

We then move to firm-level analysis. We first run OLS regressions on the productivity growth and exit rates of incumbent firms on the Cotation measure of credit constraint. We find that incumbent firms with easier access to credit (i.e. with higher rating measure) experience higher productivity growth, but we also find that incumbent firms with easier credit access experience lower exit rates, particularly the least productive firms. This we see as primary evidence we find evidence of both, the direct *investment* effect and the indirect reallocation effect of improved credit access. To reinforce our results and deal with potential endogeneity issues, we exploit a policy change which improved credit access for only a subset of incumbent firms as of a specific time. Namely, we use the 2012 Eurosystem's Additional Credit Claims (ACC) program, which extended the set of loans eligible for banks' refinancing with the ECB. As mentioned above, in the Euro Area banks can pledge corporate loans as collateral in their refinancing operations with the ECB as long as these loans are of sufficient quality, i.e. as long as the corresponding firms' ratings are sufficiently good. What the ACC program did was to extend the eligibility criterion to include a specific group of French firms (those rated 4 in Bank of France's rating system) from February 2012 onwards. We show that incumbent firms directly affected by this ACC program experienced an upward jump in productivity growth post-ACC, but we also show that these treated firms experienced lower exit rates, and particularly those treated firms that were the least productive before the introduction of ACC program.

Our analysis has implications for the debate on secular stagnation. The decline in productivity growth in most advanced countries since the 1970s may indeed be partly related to an overall easier access to credit due to financial liberalization over the period. This mechanism may have been amplified by the decrease of interest rates and the capital abundance observed in the last decade.