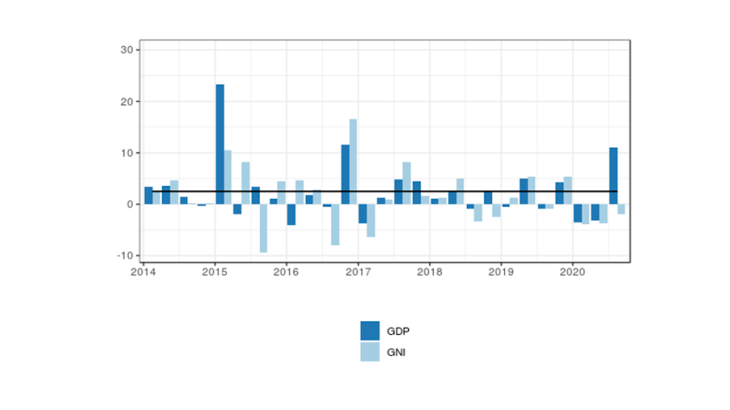

Note: GNI is equal to GDP plus primary income flows (e.g. wages, property income) received from abroad and minus primary income flows paid abroad. The strong GDP growth in Q3 2020 is attributable to the exit from lockdown following the first wave of the health crisis.

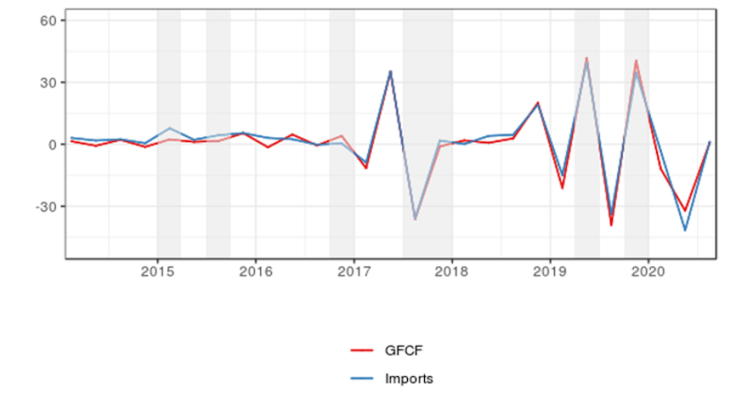

The growth of Irish Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the subject of much debate and particular attention among international organisations (Eurostat, OECD). Since 2015 (see Chart 1), quarterly growth has stood above 2.5% for eight quarters, a threshold almost twice as high as the average quarterly growth observed between 1995 and 2014. Since 1995, this threshold has been exceeded on several occasions thanks to the Ireland’s economic catch-up process and the establishment of multinationals in Ireland. What is new in the post-2015 period is the frequency and extent to which this threshold has been exceeded. These episodes are related to the relocation of sales proceeds or assets by multinationals to their Irish subsidiaries. These relocation operations are taken into account in the calculation of GDP through two channels: (i) mainly through contract manufacturing agreements which add to "physical" exports the proceeds of sales of goods and services produced abroad but owned by Irish resident units (ii) through gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) and imports of research and development (R&D) services. The magnitude of the changes in Irish GDP and its components affects euro area aggregates even though Ireland accounted for 3% of euro area GDP (in 2020). Thus, in Q2 2019, Ireland's contribution to euro area GDP amounted to 0.1 point, i.e. half of quarterly growth.

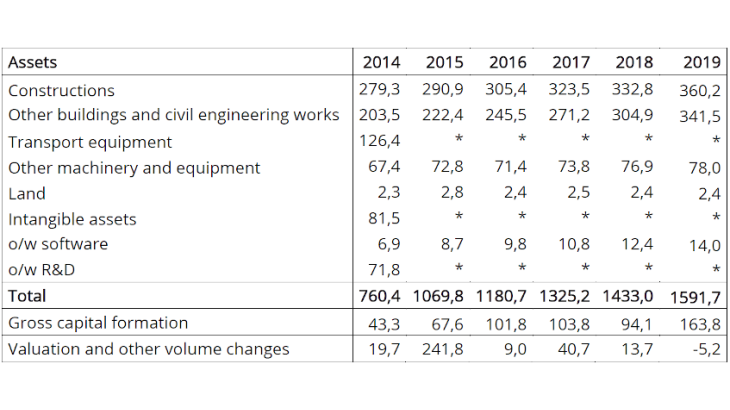

The concept of Gross National Income (GNI) is used to adjust for some of the effects of income transfers with the rest of the world. While GDP includes the income generated in Ireland but paid to non-resident agents, GNI measures the total income of agents resident in Ireland only. Although the inflows and outflows of income associated with foreign multinationals are deducted from GDP from its computation, GNI also shows a volatile pattern due to the treatment of reinvested earnings in Irish subsidiaries, i.e. the difference between the profits earned by subsidiaries in Ireland in a given year and the dividends paid to non-resident entities in that year. A large share of these reinvested earnings, which corresponds to the depreciation of intangible assets, remains within Irish resident units (Lane, 2017). In order to take account of this, the Central Statistics Office publishes annually a modified GNI, which corresponds to the GNI adjusted for, among other things, depreciation on R&D service imports.

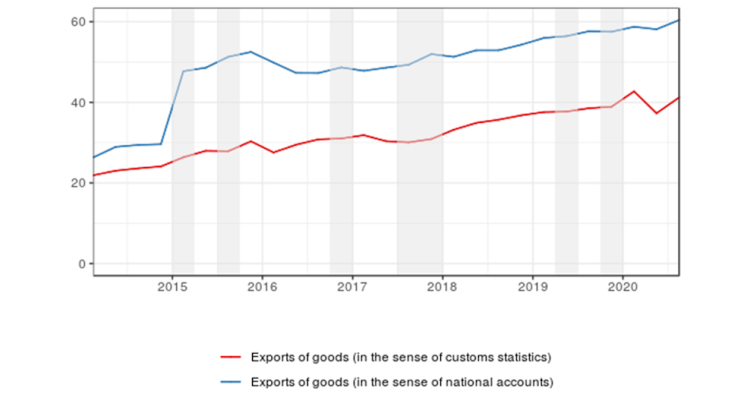

The surge in Irish exports

The recent sharp growth in Irish GDP can mainly be explained by the increase in exports in national accounts. In Q1 2015, exports jumped by more than 60% (or EUR 18 billion). This movement continued after 2015 and increased (see the quarters marked by shaded areas in Chart 2) when economic ownership of production abroad was linked to Irish subsidiaries via contract manufacturing agreements. Contract manufacturing occurs in national accounts when an Irish company resorts to a company abroad to manufacture products on its behalf, but retains economic ownership of that production. It is not always easy to determine economic ownership in the sense of national accounts and in particular to distinguish it from legal ownership. With contract manufacturing, production is physically carried out abroad but is treated for accounting purposes as Irish production followed by export. Contract manufacturing is common in the electronics sector, where the clients simply provide the necessary inputs, e.g. for the production of smartphones, and the subcontractors produce the finished products. The increase in exports via contract manufacturing agreements does not therefore correspond to trade in goods that would physically cross the Irish border but to margins earned abroad and incorporated into Irish trade in goods.

This explains why most of the variation in exports in the national accounts stems from an increase in adjustments, which includes contract manufacturing agreements, made to customs statistics, which record only trade in goods "physically" crossing the Irish border (see the difference between the two curves in Chart 2).