Sharp fall in corporate bankruptcies in 2016-2017

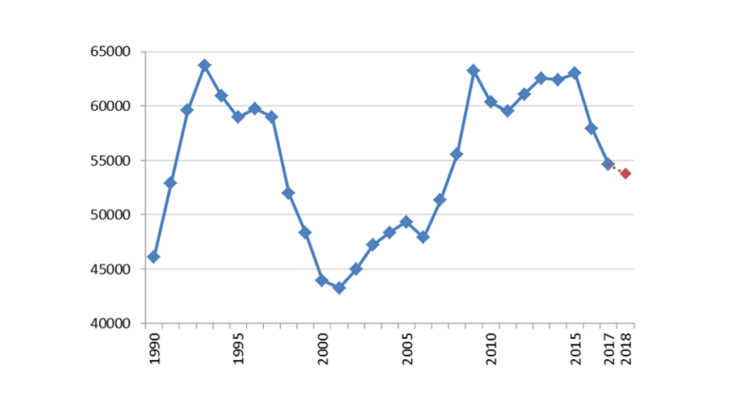

2016 and 2017 were marked by a sharp fall in the number of corporate bankruptcies, defined by receivership or liquidation proceedings (“redressements judiciaires” or “liquidations judiciaires”, Banque de France). The number of bankruptcies stood at around 54,600 in 2017, down 5.8% on 2016 and down 13.4% compared to their 2015 peak. These are the largest drops observed since 2000 (see Chart 1). Figures available for 2018 appear to confirm this trend. Indeed, at end-February 2018, we observe a 6.0% decrease compared with February 2017, as a 12-month aggregate. This decline in corporate bankruptcies since 2016 concerns most sectors of activity, with the exception of transport and agriculture, where the number of failures is continuing to rise slightly.

In order to corroborate that this fall in failures does not simply stem from a decline in the number of firms operating in the country, we calculate the bankruptcy rates by observing what happens to the companies created in a given year. This assessment confirms the decrease in bankruptcies. For example, the bankruptcy rate during the first three years of a firm's existence fell from 2.8% for companies created in 2011 to 2.4% for those created in 2014. If we only consider the first two years of a firm's existence, in order to study companies created in 2015, the bankruptcy rate declined from 1.5% in 2011 to 1.1% in 2015.

In the short term, bankruptcies have mainly negative effects…

What are the economic consequences of corporate bankrputcies? Bureau and Libert (2016) show that, on first sight, bankruptcies have direct negative effects. They result first and foremost in losses for the economic agents concerned, in particular employees, creditors and shareholders in the failing businesses.

While saving jobs is the primary aim of French bankruptcy law (see Oséo), receivership or liquidation proceedings are likely, in practice, to have a significant adverse impact on employment. It is nevertheless difficult to accurately assess the impact of bankruptcies on employment. Existing studies only present estimations of "threatened" jobs based on the staff of failing businesses. These figures – 157,000 jobs in 2017 according to Coface (2018) and 166,500 according to Altares (2018) – represent the maximum amounts since a bankruptcy does not always result in the destruction of some or all of the jobs.

… but there may also be more positive effects in the medium to long term

Public discussions often view the impact of corporate bankruptcies purely in terms of their negative short-term consequences, in particular on employment and creditors. This tends to suggest that the impact of failures on the community is negative overall. However, this point of view can be qualified if considered from a broader perspective.

Receivership and liquidation proceedings may result in a reallocation of the factors of production, capital and labour, of the failing companies toward more productive firms. Corporate bankruptcies, more broadly, participate in the overall process of reallocating resources within the economy, with the entry and exit of many companies, the failure of many new entrants and the development of efficient firms. Bartelsman et al. (2004) show that the process of creative destruction directly affects productivity via the reallocation of resources toward more productive uses, but also indirectly by encouraging established firms to raise their productivity to remain competitive vis-à-vis their new competitors.

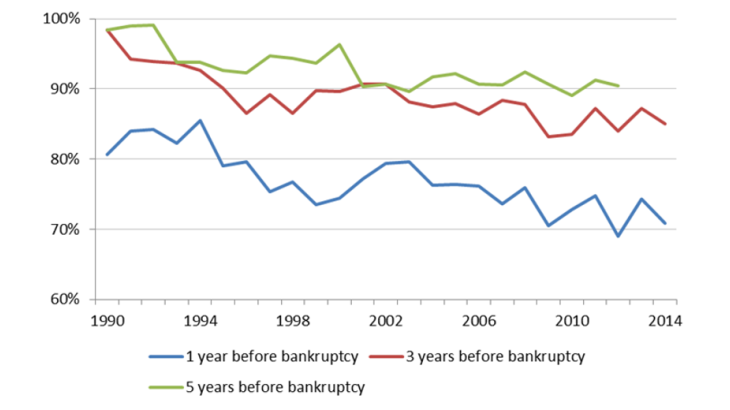

Chart 2, produced with data from the Banque de France's FIBEN company database, illustrates this point. For purely descriptive purposes, it compares the productivity of failing and non-failing businesses in the manufacturing industry during the 1990-2014 period. We take the ratio of the average productivity of firms 1 year, 3 years or 5 years before their bankruptcy to the average productivity of non-failing companies. We consider total factor productivity (TFP). TFP is the share of output which is not explained by the level of the standard inputs – capital and labour – used in the production process. It is all the more high as the inputs are used efficiently, i.e. that the level of output is high for a given level of inputs (see Libert, 2017). The results of the chart must be interpreted with caution in that they are purely descriptive and only take account of a limited share of the failing businesses (notably because firms threatened by bankruptcy generally publish less and less information as their position deteriorates, see Bureau and Libert, 2016).