While most countries have abandoned lockdowns as a policy to fight the spread of Covid-19, there is one notable and important exception -- China. Since the start of the pandemic, China has pursued a “zero-Covid” policy with the goal of achieving no new Covid infections. To that aim, it has developed a disease outbreak response system with mass testing, contact tracing, and -- if necessary -- local lockdowns. This blog explores the effect of these regional lockdowns on Chinese trade by combining province-level data on the timing and stringency of lockdowns with data on province-level international trade.

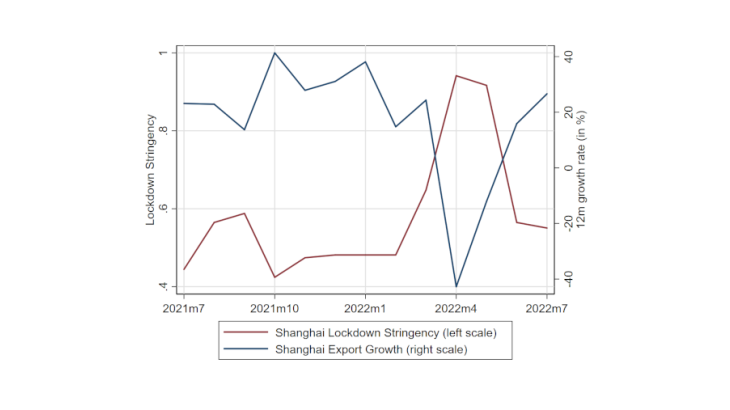

Chart 1 shows as an example changes in lockdown stringency (a measure from zero to one that captures the restrictiveness of lockdowns) and year-on-year export growth for the province of Shanghai. After initial cases were detected in early March 2022, the Shanghai authorities first responded with mobility restrictions and mass testing. Starting in early April, the entire city was placed under a particularly strict lockdown. Most schools and workplaces were closed (with the exception of necessary healthcare services), and residents were ordered to stay at home. Chart 1 shows that the Oxford stringency index rose sharply in April 2022, and year-on-year export growth of Shanghai province collapsed to -40%.

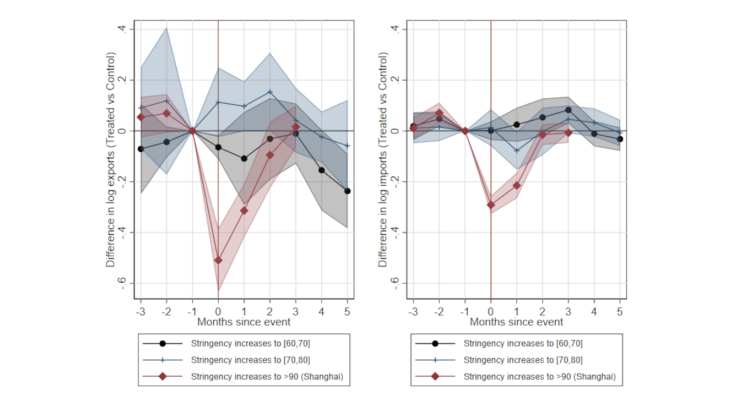

The Shanghai lockdown, however, is only one example of several regional lockdowns that Chinese authorities have implemented since mid-2020. It was also a particularly strict lockdown, as the monthly average of the Oxford stringency index for Shanghai in April 2022 rose to 0.94, far above that of any other province since the first wave. We use data from several regional lockdowns in China to estimate the effect of lockdowns on trade growth more systematically.

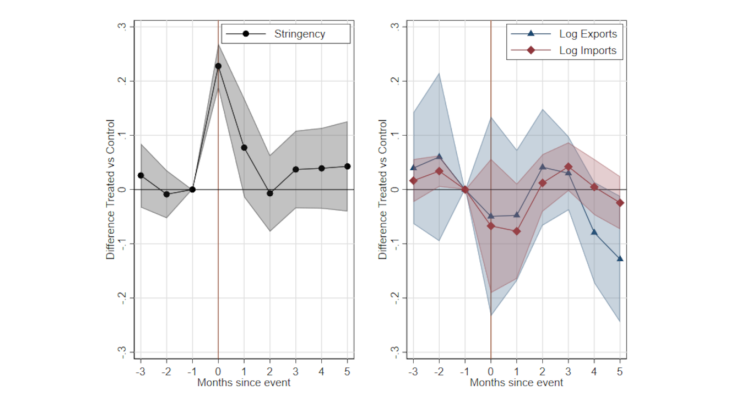

We study regional lockdowns that were implemented after the first wave, in order to focus on a time period in which lockdowns were not highly synchronised across Chinese provinces. This allows us to compare, at any point in time, the trade growth of provinces entering a lockdown (treated provinces) to those that were not (control provinces).

We start by defining regional lockdown “events” based on changes in provincial lockdown stringency. We collect data on monthly provincial lockdown stringency for China’s 31 provinces, and define a provincial lockdown as an increase in the local stringency measure of 0.2 point (on a scale from 0 to 1). Pooling data from mid-2020 to mid-2022, this defines nine provinces that experienced exactly one lockdown event and twenty control provinces without an event (two provinces with more than one event are excluded from the analysis).

The left panel of Chart 2 shows changes in stringency in treated vs control provinces, before and after a lockdown event. Prior to an event, lockdown stringency does not differ between provinces that are about to enter a lockdown and provinces that are not. As treated provinces enter a lockdown, their stringency level shoots up but reverts back to that of control provinces within 1-2 months.