- Home

- Publications et statistiques

- Publications

- Global tightening of monetary policies, ...

Global tightening of monetary policies, how are emerging countries reacting?

Post n°306. In the context of the global monetary tightening cycle, we show that most emerging countries have reacted in line with their price stability objectives. But three major emerging market economies - China, Russia and Türkiye - are currently in an easing phase for idiosyncratic reasons.

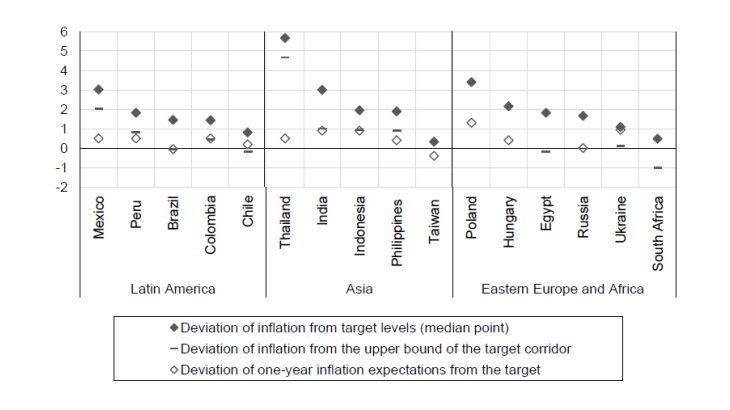

Note: The normalisation date varies across countries. For countries with an inflation target corridor, the median point is used. In this case, we have also plotted the upper and lower bounds of the target.

Normalisation cycles started at different dates, in line with objectives

In March 2021, a year before the Fed's first decision to raise rates, Brazil began to normalise the Selic rate, paving the way for other Latin American countries such as Mexico, Chile, Peru and then Colombia to follow suit the same year. After Türkiye (for which the tightening of monetary policy was short-lived, see below), Brazil was the second G20 country to start raising rates in the post-Covid period. In contrast, South-East Asian countries started to tighten monetary policy later than the United States.

Nevertheless, although the timing was different, the economic conditions prior to monetary tightening were relatively similar across emerging countries. The ex-post real rate (i.e. the nominal rate deflated by actual inflation) was between -0.5% and -3.6% before their monetary decision. The deviation of inflation from the median target rate was in the range of 0.3 to 3 percentage points (Chart 1).

Efforts to preserve the stability of emerging currencies against the dollar may explain this cautious reaction. Indeed, despite the progress made in terms of credibility by central banks that have adopted inflation targeting (Levieuge, Lucotte and Ringuedé, 2018), the risk of inflation expectations becoming unanchored and of capital outflows in the event of a widening of the interest rate differential vis-à-vis the US Fed funds remains significant (Geogieva, 2022). This is compounded by potential difficulties in determining the policy mix in some countries, as illustrated by the renewed market concerns over the inflationary risk of the new Brazilian 2023 budget.

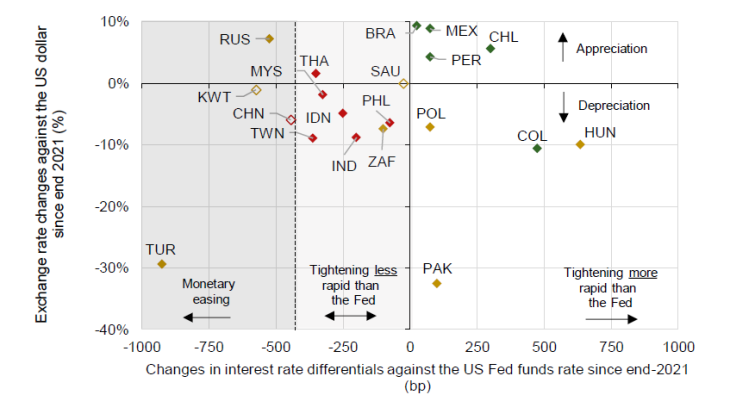

Note: Empty diamonds correspond to countries that have not adopted a floating exchange rate regime according to the IMF 2020 classification. The colour code distinguishes three geographical areas. Green corresponds to Latin American countries, red to Asian countries and yellow to African, Eastern European and Middle Eastern countries. Data at the end-January 2023.

Caution contributes to the resilience of emerging economies

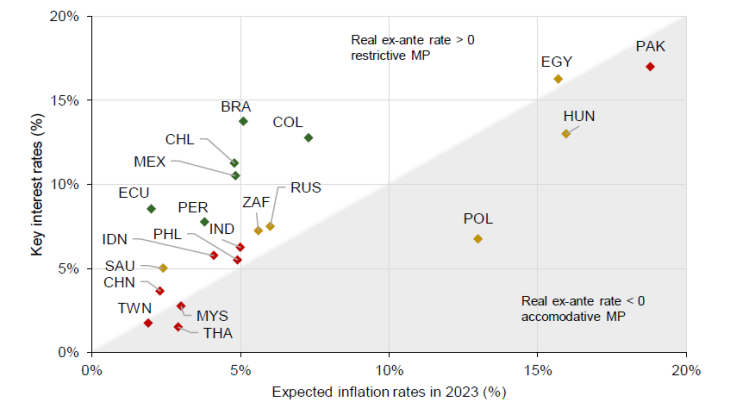

The consequences of this cautious normalisation are already visible, such as the appreciation of the Brazilian real, the Mexican and Chilean pesos and the Peruvian sol against the dollar since the end of 2021, thus limiting potential imported inflationary pressures (Chart 2). Moreover, the slowdown in inflation can already be observed in emerging markets such as Latin America, where it started to fall between 10 and 15 months after the start of their respective normalisation cycles, reflecting the classic lag in the transmission of monetary policy. Lastly, although not all ex-post real rates (deflated by actual inflation) are positive, ex-ante real rates, i.e. deflated by one-year inflation expectations, are positive in Latin America and for most of the South-East Asian countries (Chart 3). Thus, Asian countries shouldn't have to tighten their monetary policy too much in order to achieve a positive real rate, compared to Latin American countries. Indeed, the latter started to normalise their monetary policy earlier and more strongly, as in the case of Brazil, which has the tightest monetary policy in the world based on the real ex-ante rate.

Note: The colour code distinguishes three geographical areas. Green corresponds to Latin American countries, red to Asian countries and yellow to African, Eastern European and Middle Eastern countries. Data at the end-January 2023.

This cautious monetary policy response combined with better foreign exchange reserve management is contributing to the resilience of emerging markets compared to 2013 at the time of the taper tantrum. Indeed, although the foreign exchange reserves of these countries have been used to defend their currencies, they remain relatively high in Thailand and India (i.e. 9 and 10 months of imports respectively, compared to 7 and 6 months at the beginning of 2013) or have experienced a slight decline, such as in the Philippines and Malaysia (a drop of between 1 and 2 months of imports) (World Bank, 2021).

China, Türkiye and Russia form a separate group

This group is currently characterised by an accommodative monetary policy, which is at odds with the monetary policy of the vast majority of countries in the world.

In China, the adverse effects of the zero-Covid policy on growth and the increase in credit risk in the real estate sector prompted the Chinese authorities to cut key rates to 3.65% in September in order to increase the level of liquidity in the economy. The situation is therefore very different from that of other emerging countries where inflationary pressures are stronger. In January 2023, inflation stood at just 1.8% year-on-year, below the PBOC's target level of around 3%.

Since mid-2021, Türkiye’s monetary policy has been paradoxical, lowering its key interest rates by a 5 percentage points since the end of 2021, which is inconsistent with bringing inflation back to its 5% target. Indeed, inflation reached 64.3% year-on-year in January 2023 (up 28 percentage points) leading to a sharp depreciation of the lira against the dollar (-29%).

In March 2021, Russia started an interest rate normalisation cycle. But after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the subsequent Western sanctions, the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) tightened monetary policy significantly to stem capital outflows and the sharp depreciation of the rouble following the shock. Together with the introduction of capital controls, this policy quickly stabilised the currency. This was followed by a phase of rouble appreciation, fuelled by the accumulation of large trade surpluses, resulting both from the surge in oil and gas prices, Russia's main export, and the collapse of imports following Western sanctions and from the contraction in domestic demand. This paved the way for a long phase of easing for the CBR, which has cut its policy rate six times in a row since April 2022, by a total of 12.5 percentage points.

For different reasons, these three "systemically important" emerging countries are currently generating the greatest source of uncertainty in terms of short- and medium-term macroeconomic developments, which adds to the difficulties facing the global economy.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024