Patent data are commonly used in economics to measure innovation either in the IO literature to try to better understand strategies of firm regarding their investment in R&D and how they direct technical change or in the growth literature to measure technological progress. Patents are very convenient objects because they offer a wide range of information: when are they filed, who (which firm) owns the rights, where have they been granted and what patents are associated with related prior arts. One additional feature of the patent data is the underlying technological classification that has been widely studied to understand the lifecycle of some technologies.

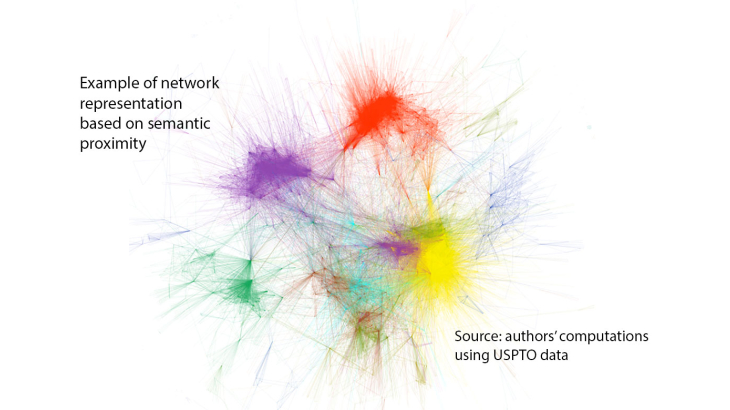

In this study, we propose an alternative classification based on semantic network analysis from patent and explore the new information emerging from it. In contrast with the regular technological classification which results from the choice of the patent reviewers, semantic classification is carried automatically based on the content of the patent abstract. Although patent officers are experts in their fields, the relevance of the existing classification is limited by the fact that it is based on the state of technology at the time the patent was granted and cannot anticipate the birth of new fields. In contrast we don't face this issue with the semantic approach. The semantic links can be clues of one technology taking inspiration from another and good predictors of future technology convergence. One can for instance consider the case of the word optic. Until more recently, this word was often associated with technologies such as photography or eye surgery, while it is now almost exclusively used in a context of transistor design and electro-optic. This semantic shift did not happen by chance but contains information on the fact that modern electronic extensively uses technologies that were initially developed in optic.

In our analysis, we consider all utility patents granted in the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) from 1976 to 2013. Just like academic articles, these patents have an abstract and a text which describe the invention that the applicant wishes to protect. For computational efficiency (there are more than 4 million patents) we had to restrict attention to abstracts in order to build our semantic network.

Our contributions are manifolds. First we define how to build a network of patents based on a classification that uses semantic information from abstracts. We describe this new classification and show that it shares some similarities with the traditional technological classification, but also have distinct features. In particular, we develop a statistical test which suggests that this classification outperforms the technological one in the sense that patents that are in the same semantic class are more likely to cite each other. Second, we provide researchers with materials resulting from our analysis, which includes: (i) a database linking each patent with its set of semantic classes and the associated probabilities; (ii) a list of these semantic classes with a description based on the most relevant keywords; (iii) a list of patent with their topological properties in the semantic network (centrality, frequency, degree, etc.).