- Home

- Deputy governors' speeches

- A single monetary policy well-calibrated...

A single monetary policy well-calibrated for the French economy

Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second Deputy Governor of the Banque de France

Published on the 29th of July 2024

By Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Deputy Governor of the Banque de France.

In his Letter to the President of the Republic in April 2024, the Governor of the Banque de France pointed out that since 1999, France's per capita purchasing power has increased by an average of 26% (cumulative), compared with just 17% in the euro area. Consumer price inflation averaged 4.4% in France between 1980 and 1998, and fell to 1.9% over the 1999-2023 period. While these gains in purchasing power and disinflation cannot be attributed solely to the euro, at least it did not hinder either of these successes.

Lower interest rates for the French economy

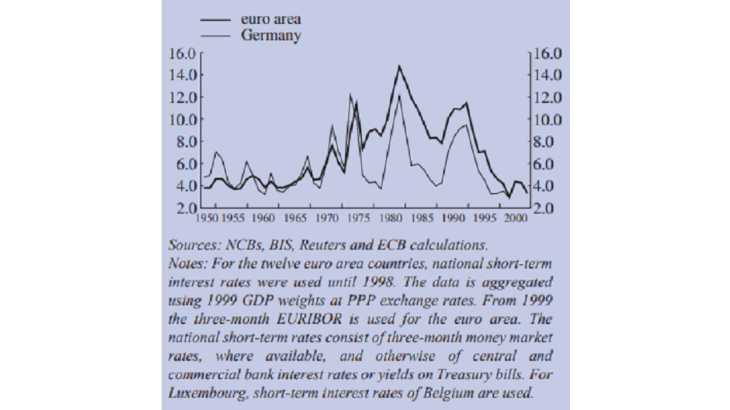

Before the euro, the exchange rate of the French franc was fixed within the European Monetary System, after having been fixed against the US dollar. French monetary policy, like that of the other ERM countries, was dictated by the constraint of not deviating too far from Germany's monetary policy, in order to avoid the risk of speculative attacks: cycles of interest rate hikes and cuts followed those of German rates (Chart 1).

This exchange rate regime was particularly restrictive and fragile when economic policies diverged. In the early 1980s, the French government's fiscal stimulus resulted in three successive devaluations of the French franc. At the start of the 1990s, the tensions this time came from Germany. For the German economy, reunification combined a positive demand shock (East German marks were converted into West German marks at a rate of 1:1, offering new purchasing power to East Germans) and a negative supply shock (the East German productive apparatus proved uncompetitive, for the same reason). In order to prevent a surge in inflation, the Bundesbank hiked interest rates sharply. The other central banks had to follow suit, as they went through a period of price deceleration and high unemployment. This episode eventually led to a currency crisis, as the markets began to question the determination of the different governments to defend their parities come what may.

Before the euro, to protect themselves against the risk of devaluation, markets demanded a risk premium for lending to the government or to the private sector in France (as well as in Italy or Belgium): Chart 1 shows that during the 1980s and at the start of the 1990s, interest rates were much lower in Germany than on average in the countries that would later form the euro area.

Interest rates converged after the currency crisis of 1992-93, when the Heads of State and Government pledged to achieve monetary union ‘by 1999 at the latest’ (Chart 2). Since then, France has benefited from interest rates that are almost identical to those in Germany, while inflation has been slightly lower. Between the pre-euro period (1980-98) and the euro period (1999-2023), the average yield on 10-year French government bond decreased by 7.1 percentage points, while inflation fell by ‘just' 2.5 percentage points. The real interest rate (nominal rate less inflation) therefore declined by 4.6 percentage points. The government, of course, has benefited, but so have households and businesses, whose borrowing rates are linked to those of the government.

Interest rates better suited to the French economy

By transferring its monetary policy to the European level, France has paradoxically benefited from a monetary policy that is better suited to its business and inflation cycles.

A traditional way of calculating the ‘appropriate’ short-term interest rate for a country's economy is to use a Taylor rule. This is a theoretical rate calculated as a weighted average of three terms: (i) the ‘neutral’ interest rate, (ii) the deviation of inflation from its target (2%), and (iii) the deviation of GDP from its potential level, these last two terms each being weighted at 50%. The nominal neutral interest rate is the sum of the real neutral rate and the inflation rate. The real neutral rate is assumed here to be equal to the growth rate of potential GDP, which reflects the economy's production capacity.

The general idea behind the Taylor rule is that the real interest rate (the difference between the nominal interest rate and inflation) should increase when inflation rises. It should also increase when GDP grows faster than its potential level, as this generally heralds a rise in inflationary pressures.

Taylor rates are calculated here separately for the euro area and for France, over the period 1999-2023, on the basis of harmonised headline inflation. There is some debate as to how to calculate potential GDP. We use the European Commission's assessment here. To avoid causing financial instability, central banks change their key rates gradually, in small steps over time. For the sake of simplicity, this gradual adjustment is not taken into account and the rates obtained are purely indicative. In the euro area, the very short-term interest rate is set by the Governing Council so as to keep inflation stable at 2%, with the constraint that it cannot fall far below zero, nor vary too rapidly over time. This justifies significant deviations from the Taylor rule.

Taylor rates follow the swings and crises in the euro area economy (Chart 3). In particular, they fell sharply during the global financial crisis (2008-09), the sovereign debt crisis (2012-15) and the Covid-19 pandemic (2020). They rose sharply during the inflationary surge of 2022.

By construction, the Taylor rate for the euro area is an average that bears no relation to the economic situation of any particular country. However, over the period 1999-2023 as a whole, and particularly in the wake of the global financial crisis, France's Taylor rate was very close to that of the euro area. The French economy benefits from the fact that it is very similar to that of the euro area as a whole, both in terms of inflation and the economic cycle. The ECB's single monetary policy, designed to meet the aggregate needs of the euro area, therefore is very likely to be appropriate for the French economy.

The French are often criticised for wanting to Europe to be like ‘a big France’, which can lead to many disappointments. Fortunately, the euro is not a ‘big franc’. It is more credible, more robust, and better recognised internationally. And it has served the needs of the French economy well since monetary unification, both on average (with much lower interest rates than before the euro) and in variation (with a monetary policy particularly well suited to the French economy). France benefits from being a ‘median’ country among its peers.

Updated on the 29th of July 2024