- Home

- Deputy governors' speeches

- Is the international monetary system “un...

Is the international monetary system “unfair”?

Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second Deputy Governor of the Banque de France

Published on the 19th of March 2025

Tribune By Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second deputy-governor of Banque de France.

March 2025

The new Trump administration’s supposed discontent with the international monetary system – judging by the views of the President’s new chief economic adviser (Miran, 2024), – has left experts scratching their heads. We’d grown accustomed to the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege”, as Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously called it in 1965: the US Treasury provides the rest of the world with a safe, liquid asset, thereby greasing the wheels of global finance, and, in return, on top of the profits from seigniorage (the greenback pays no interest to holders), the United States gets to borrow in its own currency, with no exchange rate risk and at a relatively low rate given the huge size of its public debt – more than USD 35 trillion at end-2024, or over a third of world GDP.

As Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas and Hélène Rey showed in a article de 2007,the size of the United States’ balance sheet makes it the “banker of the world”, and even a venture capital fund, with high-risk, high-yield investments on the asset side, and risk-free, low-yield bonds on the liability side. In normal times, this is a good position to be in. In times of crisis, however, the value of the nation’s assets falls, while the value of its liabilities remains the same. At the time, the authors concluded that the “exorbitant privilege” went hand in hand with an “exorbitant duty” – that of shouldering financial losses during a crisis, in the manner of an insurance firm (Gourinchas et Rey, 2022). However, over the long term, the yields on the United States’ assets exceed the yields on its liabilities, so that its net international investment position (assets less liabilities) falls to a lesser extent than its cumulated trade deficits.

Stephen Miran says this international monetary system is “unfair” as it supposedly prevents the United States from eliminating its current account deficit. With the American economy now growing more slowly than the rest of the world, due to the rise of emerging economies, global demand for liquid, dollar-denominated assets is increasing faster than US GDP. This strong demand keeps the dollar too high to reduce the massive US deficit, and interest rates too low to discourage private and public US agents from taking on more debt.

The phenomenon is well known. As far back as the 1950s, the Belgian economist Robert Triffin warned of its dangers, pointing out that without any constraints, the United States would inevitably issue too much debt. In the 1950s, the risk was that this would trigger a gold convertibility crisis, which is precisely what happened in 1971. In a floating exchange rate system, demand can only support the dollar up to a certain level of indebtedness, after which confidence collapses (Fahri et Maggiori, 2017).

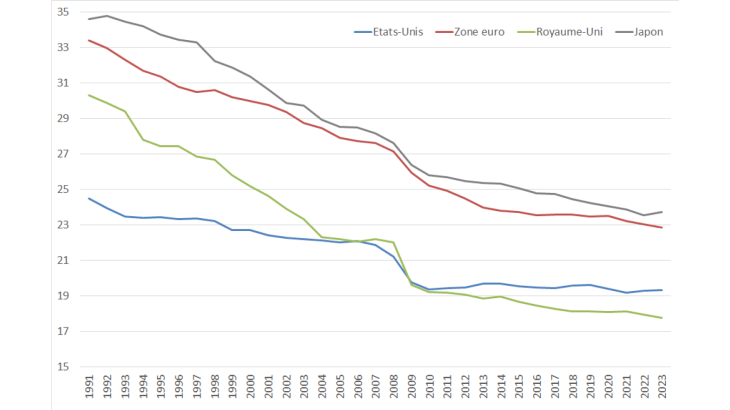

Economists usually assess the “fairness” of a system by looking at how it affects household well-being, both in average terms and in terms of the dispersion around the average (inequality). Conventional analysis of the “exorbitant privilege” would thus find that a dollar-based international monetary system (IMS) delivers long-term net benefits to the United States. By keeping the dollar overvalued relative to the size of America’s debt, it supports household purchasing power. Does deindustrialisation alter this analysis? Admittedly, America’s full employment masks a growing scarcity of stable, well-paid “good jobs”. But there is no guarantee that this is caused by the IMS, as many advanced economies are experiencing the same issue (see Chart).

Chart: Industrial jobs as a share of total employment

The dollar’s international role provides the United States with an excellent tool for exerting global pressure, via financial extraterritoriality – regardless of where a dollar transaction takes place, it is always considered to fall within the scope of US justice. This geopolitical advantage does not translate directly into purchasing power gains, or “good jobs”. However, even Stephen Miran admits that it is a major advantage in international negotiations.

The case against an IMS dominated by the dollar

In the 2000s and 2010s, critics argued that a dollar-based IMS was unsuited to an increasingly multipolar global economy. In 2009, Gouverneur Zhou (from the People’s Bank of China) memorably pointed out that it was impossible for the issuer of an international reserve currency to pursue its own domestic goals while at the same time safeguarding global financial stability. The solution he proposed was to allow Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), created in 1969, to play a central role in the IMS. The provision of global liquidity would then be divorced from the rate of growth in one country’s debt.

Another solution would be to increase the role of other international currencies, alongside the dollar, as this would boost global liquidity volumes without having to rely on a single country. Giving investors a choice of currencies in which to hold liquidity and settle transactions would also force issuers to be more disciplined, and hence mitigate the Triffin dilemma (Farhi, Gourinchas et Rey, 2011). Japan, the euro area and China have in turn, or in parallel, attempted to boost the international role of their respective currencies, but inertia linked to economies of scale and network effects has maintained the dollar’s hegemony.

Developing the euro or renminbi as an international currency would mean issuing a large quantity of homogeneous, liquid and secure assets – the equivalent of US Treasuries – and selling them throughout the financial world. China in particular would need to secure its contract law and completely liberalise capital flows, especially outflows, so that Chinese households could invest their abundant savings abroad while the rest of the world invested in China – it’s the difference between these two that makes up China’s current account surplus. This seems a rather distant prospect.

The euro is in a better position as the region already has secure contracts and free capital flows. Up to now, the euro’s international development has been hampered by its fragmented financial system and the lack of sufficient volumes of a “safe asset” that could rival US Treasuries. But things could change on both fronts.

Europe has made it a priority to reduce its financial market fragmentation under the Savings and Investments Union project, which notably includes single market supervision. Moreover, the prospect of a costly rearmament in Europe raises the possibility of a new European debt issue. In parallel, the existing large stocks of debt in euro issued separately by the European Union (EUR 689 billion), the European Financial Stability Facility (EUR 211 billion), the European Financial Stability Mechanism (EUR 78 billion) and the European Investment Bank (EUR 298 billion) could be combined to create one large pool of safe assets.

Over the longer term, the geopolitical and climate uncertainty could push Europe to finance a growing portion of its public investment jointly, by increasing the European budget and issuing common European debt. The sovereign debt of large euro area countries will also continue to provide a close substitute for a genuine European debt instrument, provided these economies comply with European fiscal rules.

In line with Ragnar Nurkse (1944), a multipolar IMS is sometimes deemed risky, as markets could switch from one currency to another at any time. However, this potential instability in portfolio allocation needs to be weighed against two stabilising factors: a multipolar system would (i) attenuate the Triffin dilemma (thanks to the diversification of liquidity sources); and (ii) provide the US with a deficit-adjustment tool: as the dollar would no longer be the only available reserve currency, it could better play its role as an adjustment variable for the US balance of payments (Bénassy-Quéré et Forouheshfar, 2015).

Charles Kindleberger (1973) introduced the concept of “hegemonic stability”, where a dominant power has an interest in maintaining the status quo and will therefore do everything it can to avoid a crisis. In practice, the US Federal Reserve acts as lender of last resort to the entire world, thanks to standing swap and repo lines with other central banks. If a country experiences a dollar shortage, the Fed will provide it with dollars for a limited period, in exchange for foreign currencies or the pledging of federal government debt securities as collateral. This solidarity between central banks is essential, and worked well during the 2008 financial crisis. However, “hegemonic stability” failed to prevent the crisis which, as has been well-documented, was rooted in excessive leverage in the US.

Could we see a Mar-a-Lago Accord?

In an essay published in November 2024, Stephen Miran proposes solving the IMS problem, not through structural changes (SDRs, multipolarisation), but with an international Plaza-style agreement. At a famous meeting at the Plaza Hotel in New York in 1985, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, West Germany and France agreed to intervene in currency markets to halt the appreciation of the dollar, which had doubled in value in five years. It was a different time, in the early days of financial globalisation (see the book published by the Peterson Institute to mark the 30th anniversary of the Plaza Accord). However, forty years later, Stephan Miran is again proposing lowering the dollar through coordinated currency market intervention by foreign central banks. To achieve this while at the same time securing funding for the budget deficit, he suggests partly offsetting coordinated dollar sales with purchases of very long-term bonds (100 years), or even perpetual bonds. He also suggests using trade tariffs to force other countries to agree.

Richard Nixon already used tariffs in 1971 to force US trading partners to revalue their currencies. Miran concedes that if other countries fail to comply immediately, higher tariffs could cause the dollar to rise; but this, he says, would only be temporary, and the ultimate goal is a weaker dollar, which would then replace the tariffs previously put in place. Alternatively, he suggests charging a “user fee” on foreign holdings of US Treasury bonds, which, on the plus side, would bring in revenue and immediately lower the dollar, but on the downside would push up market interest rates while also being easy to circumvent (see McCauley, 2025).

In addition to the doubts raised about the Plaza Accord’s actual impact on the dollar (the dollar had started to depreciate even before the Accord on 22 September 1985), the agreement left some US trading partners with painful memories. Japan had to repatriate huge amounts of savings that had been invested in the United States. The influx of capital led to a financial and property bubble, which then burst in the early 1990s, plunging Japan into long decades of deflation.

Assuming the United States actually manages to persuade its partners to repeat the experience, what might we expect? The results of research on foreign exchange interventions are hardly encouraging. The effects on currency levels in advanced economies are almost never long lasting, especially when the intervention is inconsistent with monetary policy.

Without a change in macroeconomic policies, and hence in expected yield spreads, a cheaper dollar would encourage private investors to increase their holdings, rapidly pushing the currency back up to where it was before the exchange rate agreement – especially if higher tariffs raise expectations of a dollar appreciation. But central banks are now independent, and have a clear mandate to fight inflation. They will therefore remain focused on inflationary risks in their own country or region, so the idea that there could be lasting reversal of exchange rates following an international currency agreement is highly... speculative.

Rebalancing current accounts

While the prospect of an international agreement on exchange rates seems highly uncertain, the imbalances in national current accounts are indeed very real. Whether or not they are cause for concern is open to debate, especially for an economy that borrows in its own currency. But the fact is that the new Trump administration seems particularly concerned about the country’s external deficits. How can they be reduced?

Import tariffs are clearly not the right approach. As shown by Estefania-Flores et al. (2022), protectionism reduces trade flows, GDP, investment and productivity, but has no impact on the trade balance. Charging different rates to different trading partners, as the new administration is seeking to do, is even less effective, as trade is simply rerouted via “connector countries”, allowing it to enter the United States at lower tariffs (Alfaro et Chor, 2023).

In reality, external imbalances primarily reflect macroeconomic imbalances, so cutting them up into bilateral balances does little to resolve them:

- The US deficit is due to an excess of expenditure (consumption and investment) over income (GDP). A large share of this excess stems from the budget deficit. Based on a sample of 193 countries over the 1980-2016 period, Afonso et al (2022) estimate that, all other things being equal, a rise of 1 percentage point of GDP in the budget deficit widens the current account deficit by between 0.29 and 0.45 percentage point of GDP, confirming the twin deficit hypothesis.

- In the same way, China’s surplus, to take this as an example, is caused by insufficient expenditure relative to GDP. Although it has fallen recently, China’s gross saving ratio remains very high by international standards, at 34% of disposable income in 2023, compared with 11% in the United States. While recognising the need to increase social protection to reduce Chinese households’ need for precautionary savings, China is continuing to prioritise the development of its productive apparatus. Yet the steady fall in Chinese producer prices suggests the country has excess production capacity, although weak corporate profits are doing nothing to slow investment growth.

Ultimately, the international monetary system is not “unfair”, or if it is, it is certainly not unfair for the United States. However, certain domestic economic policies are causing large external imbalances. In the short term, only by changing these policies can the United States reduce its external deficits. The dollar could then adjust endogenously rather than via some hypothetical international currency accord. It should be noted, however, that although it would help to balance the current account, a depreciation of the dollar would weigh on US household purchasing power.

Updated on the 19th of March 2025