- Home

- Deputy governors' speeches

- Don’t get mixed up with the policy-mix

Don’t get mixed up with the policy-mix

Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second Deputy Governor of the Banque de France

Published on the 18th of September 2024

Tribune By Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Second deputy-governor of Banque de France.

Having worked for the French Treasury before moving to the Banque de France, I feel legitimate to talk about the so-called policy mix – the mix of fiscal policy and monetary policy. Therefore I was happy to accept the invitation to participate in a panel on this topic during the Annual meetings of the European Economic Association in Rotterdam, together with the Governor of the Dutch Central Bank, Klaas Knot, and the Chief Economist of the European Stability Mechanism, Rolf Strauch – a panel led by Leonardo Melosi, Professor at Warwick University. The video is available here, and the slides are there.

Maastricht: a world of demand shocks

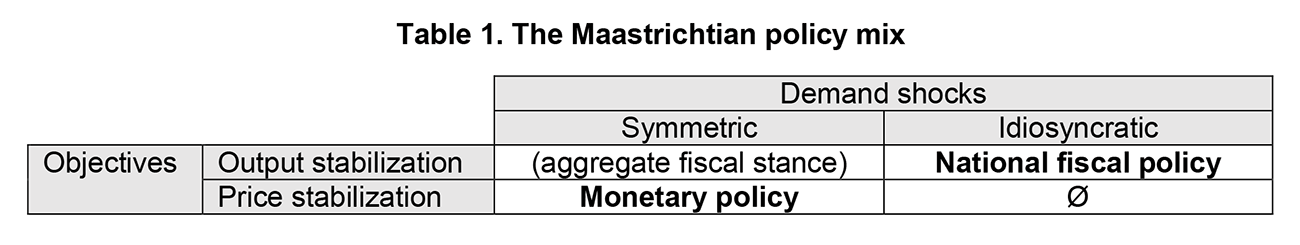

The organization of macroeconomic policies in the euro area dates back to the Maastricht treaty (1992) and the Stability and growth pact (1997). It lies along the first diagonal of Table 1: the European central bank would address aggregate shocks with the objective of stabilizing aggregate prices, whereas national governments would take care of idiosyncratic shocks – those shocks affecting specifically one country or a small number of countries -, with the objective of stabilizing the activity.

Macroeconomic stabilization policies were conceived in a world of demand shocks. For instance, a negative demand shock in theory leads to cyclical unemployment and to a fall of inflation below the central bank’s target. If the shock is symmetric, it is the task of the European Central Bank – the ECB – to lower interest rates. This will bring inflation back to target, and the same time stabilize the activity in the Euro area. If the shock is specific to a member state, the concerned government must loosen its fiscal policy. Together with automatic stabilizers which are especially powerful in Europe (net transfers received by households automatically increase in a downturn), such discretionary response will stabilize the activity in the country, and by the same token will raise the inflation rate. Symmetrically, when GDP grows faster than potential GDP and/or when inflation exceeds the target rate, monetary or fiscal tightening is required depending on whether the shock is symmetric or idiosyncratic.

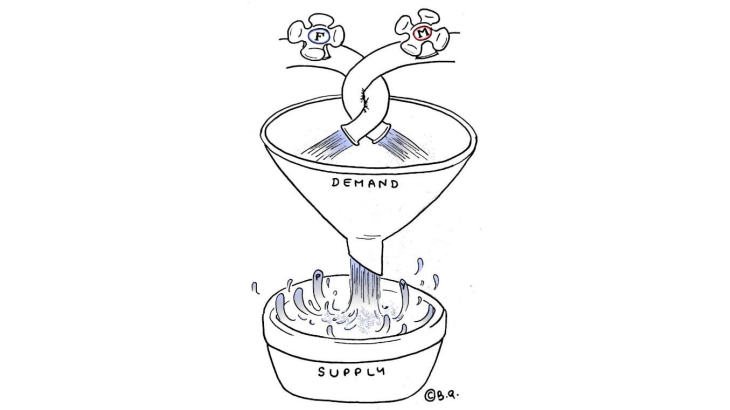

This simple setting works well when macroeconomic fluctuations are demand-driven. Since they both affect aggregate demand, fiscal and monetary policies are partly substitutes. James Tobin (1989) used the image of water flowing from a monetary tap (M) and a fiscal tap (F) into a funnel that ultimately splashes on aggregate supply (Figure 1, from Bartsch et al. 2020).

Figure 1. Tobin’s “funnel”

Source: B.Q., for Bartsch et al. (2020).

Bartsch et al. (2020) stress the importance of each tap remaining credible in order not only to work properly itself, but also to allow the other tap to work well. Credibility ensures that the impact of a policy decision is amplified by the reaction of the private sector, which does expect lower inflation when the interest rate increases, or refrains from expecting future tax hikes when public expenditure temporarily rises. Fiscal sustainability also ensures that changes in ECB’s policy rate, or announcements of such changes, will be transmitted along the yield curve.

During the 2010s, the very low level of inflation led European policymakers to explore the top-left corner of Table 1: could national fiscal policies be combined to support aggregate demand and prices at euro area level, on top of loose monetary policy, fiscal multipliers being high when interest rates are at their effective lower bound? The President of the ECB himself called for a supportive fiscal stance in 2014: “it would be helpful for the overall stance of policy if fiscal policy could play a greater role alongside monetary policy” (Draghi, 2014). The idea of an aggregate fiscal stance came up against the reluctance of national governments to deviate from their own national objectives, granted by their constituencies. It ended up with limited traction – a similar destiny as the Broad Economic Policy Guidelines that were supposed to coordinate macroeconomic policy in Article 121 of the Treaty on the functioning of the EU.

What about the bottom-right corner of Table 1? Until recently, fiscal policy had not been used to stabilize prices at national level. National governments would rather use the minimum wage or remunerations in the public sector as a way to curb inflation at national level when they feared a loss of competitiveness with respect to other Euro area countries. During the energy crisis of 2021-2023, though, several governments borrowed on financial markets to subsidize energy prices, assuming the shock would be temporary.

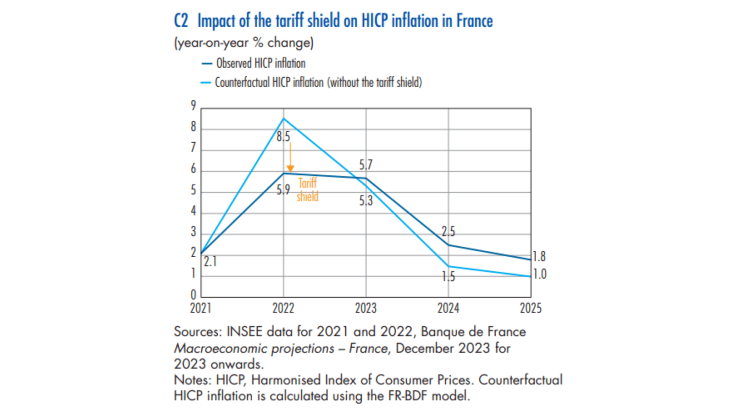

The impact of such policy is theoretically ambiguous. On the one hand, the government reduced inflation directly (although temporarily), by capping some prices. On the other hand, subsidizing purchasing power amounts to supporting aggregate demand, which pushes prices up. According to Dao et al. (2023), the former effect was dominant: government intervention reduced inflation by around 1-2 percentage points in the euro area in 2022. In the case of France, Lemoine, Petronevich and Zhutova (2024) find an impact of -2.6 pp in 2022, followed by a cumulative impact of 2.2 pp over 2023-2025, when the “shields” were progressively lifted (Figure 2). The high fiscal cost of these measures (around 1.1% of GDP in 2022 and in 2023) however makes such policy difficult to replicate, especially since it is hard to subsequently raise energy taxes when energy prices fall back below their long-term level or trend.

Figure 2.

Frankfurt getting familiar to supply shocks

Largely forgotten since the late 1970s, supply shocks are back, and they are likely to repeat themselves in the coming years, notably due to climate change and climate policies (Schnabel, 2022). How should monetary policy react?

If the shock is temporary, there is a rationale for monetary policy to “look through”: accept temporary deviations of headline inflation from its 2% target, while keeping “core inflation” (i.e. inflation excluding energy and food) constant. But even a temporary shock may de-anchor price expectations and/or trigger long-lasting second-round effects through value chains and wages. Furthermore, the volatility of headline inflation could involve resource misallocation due to expectation errors (see Ropele, Gorodnichenko and Coibion, 2024, in the case of Italy), weighing on productivity. Finally, it is difficult to assess ex ante whether a shock will be temporary or permanent, and there is a continuum of persistent but not permanent shocks in-between. Hence, central banks may be relatively busy in coping with supply shocks in the coming years, deviating from Mervyn King’s famous statement that “a successful central bank should be boring” (King, 2000).

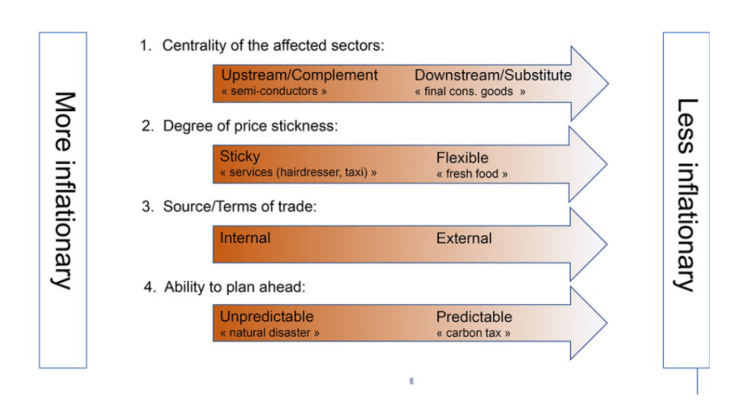

However, not all supply shocks are equal. As shown in Figure 3, borrowed from the French Governor Villeroy-de-Galhau (2024), the inflationary impact of a supply shock is less if it affects a downstream sector like tourism (or a sector with close substitutes like wine), or a sector where prices are highly flexible upward but also downward (like unprocessed food), if it comes from abroad like an oil price shock (because of the loss in terms of trade weighs on aggregate demand), or if the shock can be predicted (like an increase in the carbon tax). Hence, the reaction to supply shocks will need careful calibration on a case-by-case basis.

Figure 3. Inflationary impact of different supply shocks

A green policy mix?

How will the policy mix react to future supply shocks? A problem here is the interaction with transition policies.

Although carbon pricing is generally considered the backbone of the green transition, most experts consider that the transition will be costly for public finances (see, e.g., Mahfouz and Pisani-Ferry, 2023; French Treasury, 2023). Given the depletion of fiscal space, there is a risk that macroeconomic stabilization continues to heavily rely on monetary policy; or that fiscal policy remains too loose while monetary policy would have to be tight, to address inflationary pressure.

Some experts (e.g., Schoenmaker and van Tilburg, 2024) suggest that loose monetary policy would be favourable to the green transition by lowering the cost of capital. However, what matters for investment is the level of long-term real interest rates rather than that of short-term nominal rates. To keep long-term nominal rates at a low level, anchored price expectations are essential. Keeping them anchored requires the central bank to effectively use its instruments. As put by Governor Bailey in August in Jackson Hole, “policy does have to respond to ensure credibility is maintained” (Bailey, 2024).

As for real long-term rates, they depend on the availability of long-term savings and on the sustainability of sovereign debts. In a nutshell, the policy-mix will help the transition if it avoids creating uncertainty: credibility is an asset not only for the effectiveness of stabilization policies; it is also an asset for a smooth green transition. Don’t get mixed up with the policy-mix!

Updated on the 23rd of September 2024