- Home

- Governor's speeches

- Climate economics: from the veil of unce...

Climate economics: from the veil of uncertainty to three convictions for action

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Published on the 25th of June 2024

NGFS Annual Plenary meeting and Plenary Workshop – 25 June 2024

Speech by François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France

Ladies and Gentlemen, dear friends,

The NGFS is dear to my heart and it is always a great pleasure to be among you, even virtually. I would like to warmly thank Chair Sabine Mauderer for her invitation to speak today at the NGFS Plenary meeting.

While it began as a rather discrete initiative that eight of us took at the time in Paris, six and a half years later the NGFS has more than 140 Members. All in all, the NGFS has published more than 35 reports on topics such as supervision, transition plans, monetary policy, nature… Many of which have been praised for their quality and relevance, thanks to your work, and the global Secretariat hosted by the Banque de France. We did not take this initiative because we were climate advocates. We took it because we thought that, as central bankers and supervisors, we had a duty to care about climate change in order to fulfil our monetary and financial stability mandates.

Let me focus today on “climate economics”, and on the NGFS macroeconomic scenarios. Since their release in 2020, we have constantly worked to improve them, “vintage after vintage”.

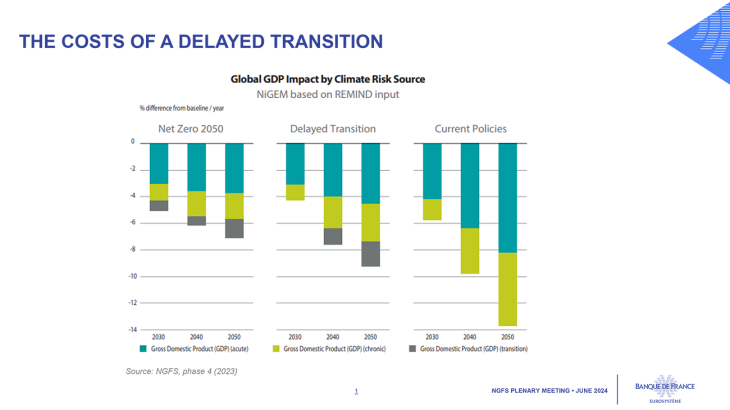

Some studiesi released or published this year suggest that the macroeconomic consequences of climate change could amount to nearly 15% of GDP by 2050, higher than the 5% of chronic impacts (in green) that feature in the current NGFS scenarios, which however account for extreme events separately.

This is unfortunately possible as the on-going work on the “damage function” assessing the impact of physical risks on the macroeconomy suggests. To remain at the forefront in this debate, the Workstream on Scenario Design and Analysis is working on new estimates of the impacts of physical risks for the next “vintage” of long-term scenarios, to be published by the end of 2024.

This is the current paradox: we could see climate change becoming less of a priority on the international and European agenda and we risk disengagement, while the need to act is becoming more pressing. Yes, there is a “veil of uncertainty” about its macroeconomic effects, due partly to future political decisions regarding climate change mitigation. For example, the initial level and change in a carbon price, or the amount of green investment and public subsidies will be especially relevant. This is why we are working on several scenarios, both over short and longer term.

But being uncertain about the combined macroeconomic effects does not mean being passive or inert. What we can already take from the scenarios is a set of three firm convictions and prescriptions for action.

1. A shock that is global and certain >>> an orderly transition

First, climate transition entails structural changes to the global economy that are both universal and significant, with an overall and possibly negative supply shock that will generate frictions and costs in terms of the necessary reallocation of production factors. Climate change – while its effects will likely go in the opposite direction – is comparable to globalisation as seen several decades ago: we knew that it would have significant effects, inevitably and everywhere, while not knowing their magnitude ex ante. This means we should organise our transition to make it as early, predictable and orderly as possible; this is not always an easy task in our democracies, which tend to be short-termist, but disorderliness would be costly.

As another consequence of this universal shock, we need to enhance international coordination: as not all countries made the same commitments, and face the same consequences and responsibilities, some are tempted by free-rider or “beggar my neighbour” behaviour. Hence climate change must be the number one priority of the “focused multilateralism” I am calling forii, be it in the G20 or in the IMF and the World Bank.

2. Higher volatility >>> strong commitment of Central Banks, but no magic wand

Second, higher volatility is likely, which means shocks on both activity and inflation. This is where we central banks have to do our job in order to maintain a solid anchoring of long term inflation expectations despite higher volatility. We cannot just look through it, since it is not an unexpected and transitory shock. Delivering on our price stability mandate and the 2% inflation target is key to avoid additional economic volatility, and to maintain moderate long term interest rates in order to fund the green transition.

That said, public debate should resist the « magic wand temptation » in which central banks are seen as being able to curb climate change on their own. I want to be crystal clear on this: monetary financing cannot fund the transition; and central banks – and green finance – cannot be the only green game in town; they cannot replace sound public policies and corporate transition plans.

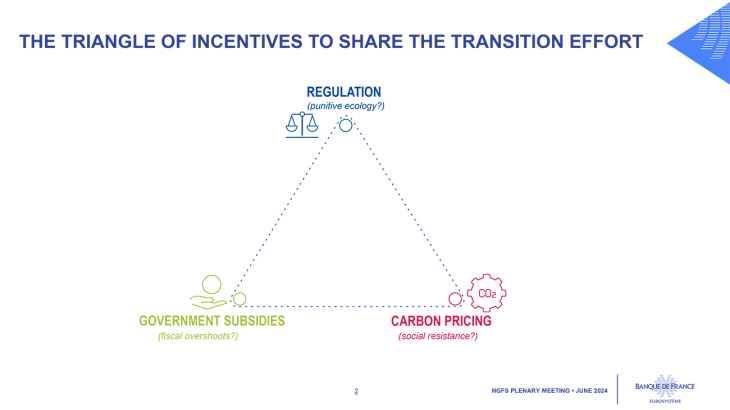

Appropriate incentives are needed.iii The difference between Europe and the United States is particularly sensitive when it comes to the form these incentives should take: regulation (as in the case of Europe’s highly ambitious “green deal”), subsidies (as with the US Inflation Reduction Act), or carbon pricing?

The three corners of this are not necessarily incompatible; each has its limits, taken in isolation: fear of “punitive ecology” in the case of regulation; fiscal overshoots and political hazards for subsidies; and strong social resistance in particular to carbon pricing. So we need a combination of these three solutions.

The fact remains that the price of carbon will have to rise: although politically unpopular, it remains an economic no-brainer. Whatever form it takes, carbon pricing will have to be global – not just national or European – and socially equitable – with a fair redistribution of part of its receipts. Europe – which is relatively ahead in this field – needs to press relentlessly for this international “new frontier”. iv Only a price signal will succeed in aligning the behaviour of firms, consumers and private finance, by making returns on green investments attractive.

On a fairer pricing of climate risk on financial markets, central bank operations and their greening have a role to play by the way, giving the right market signals and inducing changes. With Christine Lagarde, we at the ECB are pioneers in implementing a greening of our monetary operations, which should include our collateral framework.

3. Funding green investments >>> solvable through smarter finance

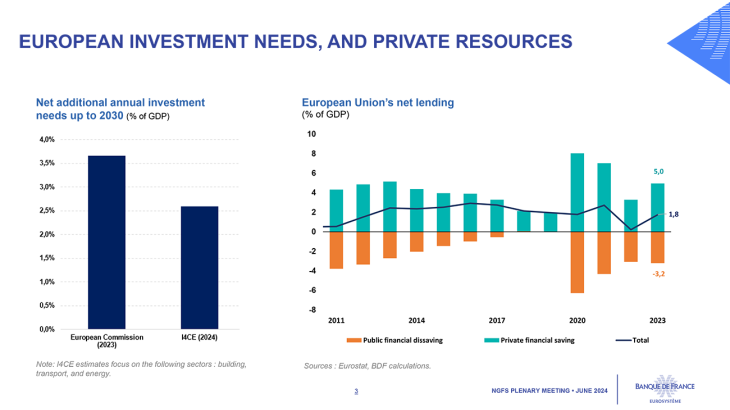

The amounts required to fund the transition are considerable: according to different estimates, the additional annual investment needs to meet our climate objectives in 2030 range from 2.6% of GDP to 3.7% of GDP in Europe. At the global level, investments in the energy sector alone will have to rise up to more than 2% of GDP in 2030, doubling from 2020 levels. vi

But the question of how to finance investments is solvable, subject to one important prerequisite: the private sector has a part to play in the effort. And it will play it more easily if climate and transition policies contribute to making these investments profitable. There is no shortage of resources. For example, Europe possesses an "unknown resource" of private savings surplus:vii after deducting public deficits, the EU's net external lending amounts to 1.8% of GDP, close to EUR 300 billion. It is therefore crucial to mobilise these resources.

Sustainable finance clearly offers a “highway” in this regard. In Europe, the introduction a comprehensive body of regulations (CSRD, supervisory expectations, green taxonomy, SFDR, etc.)viii is providing a framework to foster the development of green finance. The EU is indeed a leading issuer of green bonds, accounting for 40% of the global market in 2023.

Green securitisation is another promising lever as I have previously advocated,ix with the potential to boost bank’s capacity to finance green projects by several hundred billion euro a year in Europe.

What is true in Europe also holds elsewhere: the development of green finance, a focus on making sure that financial institutions are properly assessing and managing climate risks and planning for the transition has the potential to accelerate the local, regional and, eventually, global transition to net zero.

Therefore, provided we have the right economic incentives, the climate transition can be financed. These concrete focuses for action will enable us to overcome our natural tendency to stop listening when faced with pessimistic announcements. It was memorably depicted by Homer with Cassandra: she repeatedly tried to warn that Troy would fall should they let Ulysses’ Trojan horse get into the city. Let us heed the warnings of the scientific community, and do our part, both individually and collectively, to successfully achieve the climate transition. This is the time and place to listen to Gramsci’s famous call for “the pessimism of intelligence and the optimism of the will”. I thank you for your attention.

iBilal (A.) and Känzig (D.), The Macroeconomic Impact of Climate Change: Global vs. Local Temperature, NBER Working Paper, May 2024 ; Kotz (M.), Leermann (A.) and Wenz (L.), The economic commitment of climate change, Nature, 17 April 2024

iiVilleroy de Galhau, F., How central banks should face instability and fragmentation, speech, 12 April 2023

iiiFrance and Europe: from crisis management to a longer-term ambition, Letter to the President of the Republic, 22 April 2024.

ivSee in particular the working paper by V. Gaspar (IMF) and R. de Mooij (IMF), "How does decarbonization change the fiscal equation?" Peterson Institute, November 2023.

vVilleroy de Galhau, Financing the climate transition: building bridges between needs and resources, speech, 22 April 2024.

viNGFS, scenarios for central banks and supervisors, Workstream on Scenario Design and Analysis, November 2023.

viiFinancial savings based on national accounts: savings after investment and capital transfers.

viiiSustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

ixVilleroy de Galhau, From a Capital Markets Union to a genuine Financing Union for Transition, speech, 23 February 2024.

Updated on the 25th of July 2024